Supported by

Mother Wonders if Psychosis Drug Helped Kill Son

At first, the psychiatric drug Zyprexa may have saved John Eric Kauffman’s life, rescuing him from his hallucinations and other symptoms of acute psychosis.

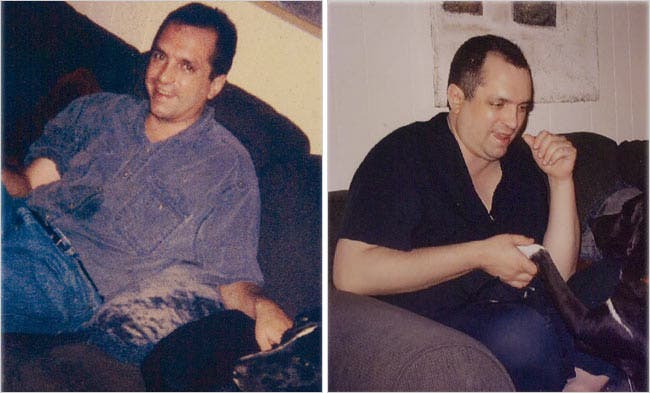

But while taking Zyprexa for five years, Mr. Kauffman, who had been a soccer player in high school and had maintained a normal weight into his mid-30s, gained about 80 pounds. He was found dead on March 27 at his apartment in Decatur, Ga., just outside Atlanta.

An autopsy showed that the 41-year-old Mr. Kauffman, who was 5 feet 10 inches, weighed 259 pounds when he died. His mother believes that the weight he gained while on Zyprexa contributed to the heart disease that killed him.

Eli Lilly, which makes Zyprexa, said in a statement that Mr. Kauffman had other medical conditions that could have led to his death and that “Zyprexa is a lifesaving drug.” The company said it was saddened by Mr. Kauffman’s death.

Advertisement

No one would say Mr. Kauffman had an easy life. Like millions of other Americans, he suffered from bipolar disorder, a mental illness characterized by periods of depression and mania that can end with psychotic hallucinations and delusions.

After his final breakdown, in 2000, a hospital in Georgia put Mr. Kauffman on Zyprexa, a powerful antipsychotic drug. Like other medicines Mr. Kauffman had taken, the Zyprexa stabilized his moods. For the next five and a half years, his illness remained relatively controlled. But his weight ballooned — a common side effect of Zyprexa.

His mother, Millie Beik, provided information about Mr. Kauffman, including medical records, to The New York Times.

For many patients, the side effects of Zyprexa are severe. Connecting them to specific deaths can be difficult, because people with mental illness develop diabetes and heart disease more frequently than other adults. But in 2002, a statistical analysis conducted for Eli Lilly found that compared with an older antipsychotic drug, Haldol, patients taking Zyprexa would be significantly more likely to develop heart disease, based on the results of a clinical trial comparing the two drugs. Exactly how many people have died as a result of Zyprexa’s side effects, and whether Lilly adequately disclosed those risks, are central issues in the thousands of product-liability lawsuits pending against the company, and in state and federal investigations.

Because Mr. Kauffman also smoked heavily for much of his life, and led a sedentary existence in his last years, no one can be sure that the weight he gained while on Zyprexa caused his heart attack.

Advertisement

Zyprexa, taken by about two million people worldwide last year, is approved to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Besides causing severe weight gain, it increases blood sugar and cholesterol in many people who take it, all risk factors for heart disease.

In a statement responding to questions for this article, Lilly said it had reported the death of Mr. Kauffman to federal regulators, as it is legally required to do. The company said it could not comment on the specific causes of his death but noted that the report it submitted to regulators showed that he had “a complicated medical history that may have led to this unfortunate outcome.”

“Zyprexa,” Lilly’s statement said, “is a lifesaving drug and it has helped millions of people worldwide with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder regain control of their lives.”

Documents provided to The Times by a lawyer who represents mentally ill patients show that Eli Lilly, which makes Zyprexa, has sought for a decade to play down those side effects — even though its own clinical trials show the drug causes 16 percent of the patients who take Zyprexa to gain more than 66 pounds after a year.

Advertisement

Eli Lilly now faces federal and state investigations about the way it marketed Zyprexa. Last week — after articles in The Times about the Zyprexa documents — Australian drug regulators ordered Lilly to provide more information about what it knew, and when, about Zyprexa’s side effects.

Lilly says side effects from Zyprexa must be measured against the potentially devastating consequences of uncontrolled mental illness. But some leading psychiatrists say that because of its physical side effects Zyprexa should be used only by patients who are acutely psychotic and that patients should take other medicines for long-term treatment.

“Lilly always downplayed the side effects,” said Dr. S. Nassir Ghaemi, a specialist on bipolar disorder at Emory University in Atlanta. “They’ve tended to admit weight gain, but in various ways they’ve minimized its relevance.”

Dr. Ghaemi said Lilly had also encouraged an overly positive view of its studies on the effectiveness of Zyprexa as a long-term treatment for bipolar disorder. There is more data to support the use of older and far cheaper drugs like lithium, he said.

Last year, Lilly paid $700 million to settle 8,000 lawsuits from people who said they had developed diabetes or other diseases after taking Zyprexa. Thousands more suits are still pending.

Advertisement

But Ms. Beik is not suing Lilly. She simply wants her son’s case to be known, she said, because she considers it a cautionary tale about Zyprexa’s tendency to cause severe weight gain. “I don’t think that price should be paid,” she said.

Mr. Kauffman’s story, like that of many people with severe mental illness, is one of a slow and steady decline.

Growing up in DeKalb, Ill., west of Chicago, he acted in school plays and was a goalie on the soccer team. A photograph taken at his prom in 1982 shows a handsome young man with a messy mop of dark brown hair.

But in 1984, in his freshman year at Beloit College in Wisconsin, Mr. Kauffman suffered a breakdown and was found to have the most severe form of bipolar disorder. He returned home and, after medication stabilized his condition, enrolled in Northern Illinois University. He graduated from there in 1989 with a degree in political science.

For the next year, he worked as a bus driver ferrying senior citizens around DeKalb. In a short local newspaper profile of him in 1990, he listed his favorite book as “Catch-22,” his favorite musician as Elvis Costello, and his favorite moment in life as a soccer game in which he had made 47 saves. A few months later, he followed his mother and stepfather to Atlanta and enrolled in Georgia State University, hoping to earn a master’s degree in political science.

Advertisement

“He wanted so much to become a political science professor,” Ms. Beik said.

But trying to work while attending school proved to be more stress than Mr. Kauffman could handle, Ms. Beik said. In 1992, he suffered his most severe psychotic breakdown. He traveled around the country, telling his parents he intended to work on a political campaign. Instead, he spent much of the year homeless, and his medical records show that he was repeatedly admitted to hospitals.

Mr. Kauffman returned home at the end of 1992, but he never completely recovered, Ms. Beik said. He never worked again, and he rarely dated.

In 1994, the Social Security Administration deemed him permanently disabled and he began to receive disability payments. He filed for bankruptcy that year. According to the filing, he had $110 in assets — $50 in cash, a $10 radio and $50 in clothes — and about $10,000 in debts.

From 1992 to 2000, Mr. Kauffman did not suffer any psychotic breakdowns, according to his mother. During that period, he took lithium, a mood stabilizer commonly prescribed for people with bipolar disorder, and Stelazine, an older antipsychotic drug. With the help of his parents, he moved to an apartment complex that offered subsidized housing.

But in late 1999, a psychiatrist switched him from lithium, which can cause kidney damage, to Depakote, another mood stabilizer. In early 2000, Mr. Kauffman stopped taking the Depakote, according to his mother.

Advertisement

As the year went on, he began to give away his possessions, as he had in previous manic episodes, and became paranoid. During 2000, he was repeatedly hospitalized, once after throwing cans of food out of the window of his sixth-floor apartment.

In August, he was institutionalized for a month at a public hospital in Georgia. There he was put on 20 milligrams a day of Zyprexa, a relatively high dose.

The Zyprexa, along with the Depakote, which he was still taking, stabilized his illness. But the drugs also left him severely sedated, hardly able to talk, his mother said.

“He was so tired and he slept so much,” Ms. Beik said. “He loved Shakespeare, and he was an avid reader in high school. At the end of his life, it was so sad, he couldn’t read a page.”

Advertisement

In addition, his health and hygiene deteriorated. In the 1990 newspaper profile, Mr. Kauffman had called himself extremely well-organized. But after 2000, he became slovenly, his mother said. He spent most days in his apartment smoking.

A therapist who treated Mr. Kauffman while he was taking Zyprexa recalls him as seeming shy and sad. “He was intelligent enough to have the sense that his life hadn’t panned out in a normal fashion,” the therapist said in an interview. “He always reminded me of a person standing outside a house with a party going on, looking at it.”

The therapist spoke on the condition that her name not be used because of rules covering the confidentiality of discussions with psychiatric patients.

As late as 2004, Mr. Kauffman prepared a simple one-page résumé of his spotty work history — evidence that he perhaps hoped to re-enter the work force. He never did.

As Mr. Kauffman’s weight increased from 2000 to 2006, he began to suffer from other health problems, including high blood pressure. In December 2005, a doctor ordered him to stop smoking, and he did. But in early 2006, he began to tell his parents that he was having hallucinations of people appearing in his apartment.

Advertisement

On March 16, a psychiatrist increased his dose of Zyprexa to 30 milligrams, a very high level.

That decision may have been a mistake, doctors say. Ending smoking causes the body to metabolize Zyprexa more slowly, and so Mr. Kauffman might have actually needed a lower rather than higher dose.

A few days later, Mr. Kauffman spoke to his mother for the last time. By March 26, they had been out of contact for several days. That was unusual, and she feared he might be in trouble. She drove to his apartment building in Decatur the next day and convinced the building’s manager to check Mr. Kauffman’s apartment. He was dead, his body already beginning to decompose.

An autopsy paid for by his mother and conducted by a private forensic pathologist showed he had died of an irregular heartbeat — probably, the report said, as the result of an enlarged heart caused by his history of high blood pressure.

Ms. Beik acknowledged she cannot be certain that Zyprexa caused her son’s death. But the weight gain it produced was most likely a contributing factor, she said. And she is angry that Eli Lilly played down the risks of Zyprexa. The company should have been more honest with doctors, as well as the millions of people who take Zyprexa, she said.

Instead Lilly has marketed Zyprexa as safer and more effective than older drugs, despite scant evidence, psychiatrists say.

Advertisement

Ms. Beik notes that Stelazine — an older drug that is no longer widely used — stabilized Mr. Kauffman’s illness for eight years without causing him to gain weight.

“He was on other drugs that worked,” she said.

A front-page article on Thursday about the side effects of the psychiatric drug Zyprexa misstated the name of a older drug tested against Zyprexa in a federally sponsored clinical trial. It was perphenazine (also called Trilafon), not Stelazine.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at nytnews@nytimes.com.Learn more

Advertisement