Supported by

U.S. Wonders if Drug Data Was Accurate

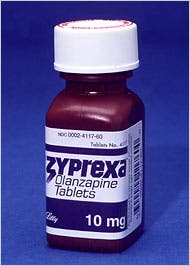

The Food and Drug Administration is examining whether Eli Lilly & Company provided it with accurate data about the side effects of the antipsychotic drug Zyprexa, a potent medicine that has been linked to weight gain and diabetes.

The F.D.A. has questions about a Lilly document from February 2000 in which the company found that patients taking Zyprexa in clinical trials were three and a half times as likely to develop high blood sugar as those who did not take the drug.

That document was not submitted to the agency. But a few months later, Lilly provided data to the F.D.A. that showed almost no difference in blood sugar between patients who took Zyprexa and those who did not.

The F.D.A. confirmed its inquiry in response to questions from The New York Times. The agency said it had not yet decided whether to take any action against Lilly.

Advertisement

“The F.D.A. continues to explore the concerns raised recently regarding information provided to the F.D.A. on Zyprexa’s safety,” Dr. Mitchell Mathis, a deputy director in the psychiatry division of the agency’s center for drug evaluation and research, said.

A Lilly spokesman, Phil Belt, said the company had rechecked its database and found errors in the original statistics. The data submitted later was accurate, Mr. Belt said.

But the 2000 document said that its figures had already been checked for error. The Times disclosed the existence of the document in an article last December.

The discrepancy between Lilly’s initial data and what it later submitted came at a time when Zyprexa’s sales were soaring, even as some doctors and foreign regulatory agencies were questioning the drug’s safety.

The F.D.A. has never concluded that Zyprexa causes diabetes more than other widely used psychiatric drugs, although the American Diabetes Association has.

Advertisement

Zyprexa remains Lilly’s top-selling drug, with $4 billion in worldwide annual sales. But prescriptions in the United States have fallen nearly 50 percent since 2003 amid the safety concerns.

Zyprexa and other antipsychotics are intended to quell the hallucinations and delusions associated with schizophrenia and to treat some cases of mania.

The document from 2000 and others were provided to The Times by James B. Gottstein, a lawyer who represents mentally ill people he says are forced to take psychiatric medications against their will.

Besides the F.D.A. inquiry, Lilly is facing federal and state investigations into the way it marketed and promoted Zyprexa. The company has already agreed to pay $1.2 billion to settle 28,500 lawsuits from people who contend that they developed diabetes or other diseases after taking the drug. At least 1,200 more lawsuits are pending.

Mr. Belt, the Lilly spokesman, said in a statement that the company properly marketed Zyprexa and disclosed its side effects to the F.D.A. and doctors.

Advertisement

“Lilly always cooperates fully with requests for information from the F.D.A.,” he said, “and that includes any requests regarding information on Zyprexa. Lilly is forthcoming with all relevant clinical data on all of our products.”

Lawyers who represent drug companies said the F.D.A. largely depended on the companies to be honest about the side effects of their drugs. With a staff of fewer than 3,000, including support personnel, the agency’s drug division oversees more than 12,000 prescription medicines and 400 nonprescription drugs.

In most cases, said William W. Vodra, senior counsel at the law firm of Arnold & Porter and a former F.D.A. associate chief counsel, it does not perform detailed audits of clinical trials or independently check the integrity of the data that companies send to it.

“There’s no way they could police the system with the resources they have,” Mr. Vodra said. Companies provide the agency’s scientists with so much information that “there is a point at which you can’t even think about what they’ve given you,” he added, “let alone what’s behind that stuff that they may not have given you.”

Advertisement

Robert A. Dormer, a partner in the law firm of Hyman, Phelps & McNamara, who represents drug companies, said that the companies did not have to provide every analysis they performed to the F.D.A. “Companies do lots of drafts of things,” Mr. Dormer said.

The Zyprexa document that has aroused the most interest at the F.D.A. is a Feb. 21, 2000, paper in which Lilly scientists discussed whether Zyprexa’s label should be changed to alert doctors of the risk of hyperglycemia, or high blood sugar, associated with the drug.

The paper showed that 154 of 4,234 patients, or 3.6 percent, who took Zyprexa in clinical trials developed high blood sugar. Only 1.1 percent of patients who took a placebo developed the condition.

Doctors have said that difference is worrisome because most patients in the clinical trials were taking Zyprexa for only a few weeks or months. Untreated hyperglycemia can eventually lead to diabetes, a disease in which the body’s insulin-producing cells die and patients lose the ability to regulate their blood sugar. Diabetes is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States.

The data that Lilly provided to the F.D.A. was notably different from the results discussed in the February 2000 paper, with the gap between the two patient groups much narrower. The company told the agency that patients taking Zyprexa developed high blood sugar at a 3.1 percent rate, while those taking the placebo had a 2.5 percent rate.

Advertisement

Mr. Belt said that after the February 2000 paper, Lilly performed a final quality check of the data and discovered that some patients had been incorrectly included in the analysis, while others had been excluded.

“The original data referred to in the memo was a preliminary analysis, not the final accurate analysis that was provided to the F.D.A., and is therefore very misleading,” he said.

The Times reported in December on the existence of the February 2000 document, as well as other company documents and e-mail messages that contradicted public statements by Lilly about Zyprexa’s risks.

Lilly has said that the documents and e-mail messages were taken out of context and do not present a balanced view of Zyprexa’s risks and benefits. A federal judge has criticized The Times for violating a protective order that covered the documents.

Advertisement