In June 1992, not long after the place closed down, a Harvard-trained psychologist named Sergio Pirrotta walked out of Danvers State Hospital for the last time. The psychiatric facility, at this late date, was a baggy old thing, rectangled into a field just north of Boston; whole wings were barely occupied, and vandals had already begun to rip out the mantelpieces and furniture. The hospital had been slowly, incrementally shutting down for a decade, and the patients that remained were the hardest cases, mostly schizophrenics and those with disorders too dense and weird to classify. But now, as Pirrotta took a walk around the campus, even those patients were gone: released into the larger world to fend for themselves or bused to hospitals where the staffs had little psychiatric training.

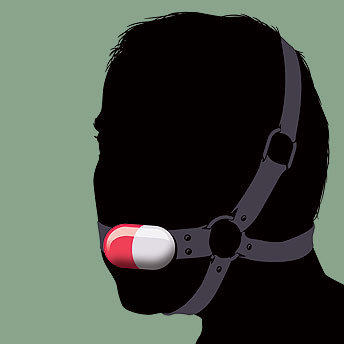

Pirrotta had come to Danvers in the mid-1970s to rehabilitate children whom the courts had declared insane. Back then the place was overpopulated, the halls packed with madmen who would wander around smoking cigarettes, leering and lunging at the kids. In those days, the drugs used to treat mental illness were crude and ugly things. Thorazine was the best, and it made you into a ghouled and lifeless ogre — your face seized up involuntarily, you kept shuffling around, you were an emotional drone. But gradually the medications got a little bit better, the pharmacology more precise. First there was haloperidol, similar to Thorazine but with less-vivid side effects. Then clozapine, which had at first seemed a wonder drug, before it turned out to trigger a potentially fatal immune deficiency in two cases out of a hundred.

The patients at Danvers, their symptoms softened by the new medications, began to venture forth, almost miraculously, into the world beyond the hospital. Pirrotta took a group that included schizophrenics to a children's camp in New Hampshire, off-season, where they spent a week cleaning and grooming the grounds. "For most of them, it was the first time they'd been out of an institution in their adult lives," he recalls. But the state's budget crunchers had wanted to close places like Danvers for years — pills, after all, were far cheaper than hospitals — and the new drugs made the move clinically defensible. To the staff at Danvers, it seemed as if the state had abandoned its responsibilities to the mentally ill. "It felt like we'd been sold a bill of goods," Pirrotta says. "It felt like a betrayal."

By 1992, when Danvers closed, something even more vivid and hopeful was looming: A whole new class of drugs, called atypical antipsychotics, were being tested in clinical trials. The atypicals held the promise of a more perfect tranquilizer, one that would calm the storms of schizophrenia while eliminating the side effects that made the older drugs so despised. Psychiatrists reserved their greatest excitement for a molecule being developed by Eli Lilly, a pharmaceutical company based in Indianapolis. The new chemical mirrored the powers of clozapine but without its fatal flaw. It was called olanzapine, and the scientists working on it believed it might be the One.

Dr. William Wirshing, a UCLA psychiatrist who had a grant from Lilly to conduct clinical trials on olanzapine, was one of those enthused by the early results. He believed the hype was warranted, and Lilly was flying him around the country to brief other psychiatrists on his work and to seed excitement for the coming medication. Then one morning in 1995, as Wirshing was driving to LAX to catch a pre-dawn flight, a story came on the radio about olanzapine. Wirshing listened in astonishment as a top Lilly executive announced the company's plans for the new drug, which it was preparing to market under the name Zyprexa.

"He says it's got the potential to be a billion-dollar-a-year drug," Wirshing recalls. "I almost pulled off the road and crashed into the side rail." At the time, the entire market for atypical antipsychotics was only $170 million. "How the hell do you make $1 billion?" Wirshing thought. "I mean, who are we gonna give it to? It's not like we're making any more schizophrenic brains."

There is a well-known feature of medical science called the placebo effect, which suggests that, in a clinical trial, patients who are told they are being medicated but are in fact given only a sugar pill will see their symptoms improve, merely out of the misplaced conviction that they are being healed. During the late 1990s, and then with increasing speed during the current decade, Wirshing and other psychiatrists watched as the market for atypical antipsychotics swelled well beyond its marked territory, far exceeding the country's supply of schizophrenic brains — past $2 billion a year, $5 billion, $10 billion, all the way to $16 billion. What had begun as niche drugs are now the third-largest class of medication in the world, their sales greater than those of the antidepressants. The mechanisms used to leverage this growth were in some ways the most modern and perfect the pharmaceutical industry had developed, but they were also, according to state and federal prosecutors, illegal. Lilly has already agreed to pay $2.6 billion to settle charges that it built the market for Zyprexa first by concealing its side effects, and then by marketing it "off-label," for diseases for which it had not been approved.

"It was a very clever sort of con," says Dr. Peter Tyrer, a leading psychiatric researcher at Imperial College in London who wrote in the latest issue of the respected medical journal The Lancet about a new study that debunks the effectiveness of the atypicals. "Almost the whole scientific community was conned into thinking — as a consequence of good marketing — that this was a different and better set of drugs. The evidence, as it's all added up, has shown this to be untrue."

Eli Lilly insists that it has not marketed Zyprexa off-label and that it has accurately represented the drug's side effects. But some medical researchers who have studied the atypical antipsychotics say that, in the final tally, the drugs, which have already been linked to some deaths, may eventually be responsible for tens of thousands of cases of diabetes and other potentially fatal diseases. And despite their early promise for treating schizophrenia, the drugs have not even performed any better than the crude and imprecise earlier medications that preceded them. "We have been paying $16 billion a year instead of $2 billion a year for drugs that seem to be no better and might be worse," says Douglas Leslie, a researcher at the Medical University of South Carolina who contributed to an extensive federal study of the drugs. The story of how Zyprexa and other atypicals became a multibillion-dollar market suggests that the medical community — doctors, researchers, the institutions that back them — may be themselves prone to a placebo effect: the willed conviction that a new drug, presented as a breakthrough, must in fact be one, that a product sold as healing must in fact do good.