Drugged into Submission

Monday, April 25

| ||||

|

Doctors prescribed sedatives and powerful, mood-altering medications for nearly 700 Ohio babies and toddlers on Medicaid last summer, according to a Dispatch review of records.

There’s no doubt that mentalhealth drugs can help troubled youngsters, whether they’re on the government insurance program for the poor or not. But dozens of advocates, child-welfare workers and psychiatrists interviewed by The Dispatch question the wisdom of prescribing potent medications, most of which have never been tested on kids, for so many young, vulnerable children.

‘‘It’s shocking," said Dr. Ellen Bassuk, associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. ‘‘Who’s really being helped by these children being drugged? The babies? Or their caregivers?

‘‘These medications are not benign; they can have dangerous side effects and have to be closely monitored."

Federal officials have long required that drugs be screened for safety in adults. But less than one-fourth have been tested on children.

‘‘Kids are not little adults," said Dr. Patricia Goetz, assistant medical director for the state Department of Mental Health. ‘‘Children’s brains are different. They don’t fully develop until after adolescence."

That often leaves doctors with more questions than answers about the long-term effects of many drugs on children.

Physical side effects can range from headaches, nausea and weight gain to heart attacks, liver damage and sudden death.

Psychological effects remain a mystery. But several antidepressants carry FDA-required warnings that they can increase the risk of suicide. Some antipsychotics have caused learning problems in 3- to 6-year-olds.

‘‘It seems a growing number of yesterday’s wonder drugs, such as Adderall, have turned into today’s suicide pills," said Laura Wissler, a parent advocate for the Mental Health Association of Summit County.

In February, Canada pulled the attention-deficit hyperactivity drug from the market, saying it was related to 20 sudden deaths. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration reviewed those deaths last year and determined Adderall should carry a warning that it not be prescribed to people with heart trouble.

A Westerville woman watched her daughter’s high spirits disappear under the influence of Paxil, which she was taking for anxiety.

‘‘The stuff did not work for her, and it was in weaning her after only two apparently ineffective weeks that we saw the horrifying effects we now know are typical," said Lucy, who asked that her full name not be used, to protect her child’s identity.

Lucy noticed the drug’s effect 2½ years ago, the night of her daughter’s 11 th birthday.

‘‘My wonderfully precocious child told me, ‘I don’t think it would be so awful to die, except I couldn’t bear what it would do to you,’ " she said. ‘‘I’ve never seen her so miserable and hopeless."

Those scary days are long gone, but Lucy and her daughter can’t forget the memory.

Drugs

become

first

option

Many advocates worry that mental-health disorders are overdiagnosed and youths aren’t given options such as counseling.

‘‘Medications only help control symptoms," said Yvette McGee Brown, president of the Center for Child and Family Advocacy at Children’s Hospital. ‘‘Counseling helps children control their behaviors, feelings and thoughts. You can’t put kids on a bunch of drugs, then take them off thinking they’ll know how to cope."

Advocates are especially concerned about the very young.

‘‘Research shows that 0 to 3 are the most critical years for the development of children and their success in the future," said Patricia Amos, a member of the Family Alliance to Stop Abuse and Neglect in New Jersey.

‘‘How do we know we’re not messing that up by starting children on one medication, then adding on another and another, until their brains are hyperaroused, overstimulated and permanently altered?"

But others say the more early intervention, the better.

‘‘The biggest public-health crisis facing the state and nation is the number of children with mental illness who fail to receive any care or treatment," said Michael Hogan, director of the Ohio Department of Mental Health.

‘‘It’s true children are more likely to get medication than counseling or other behavioral therapy if they go to their pediatrician or family doctor. But at the end of the day, meds are quite safe and effective."

There is such a shortage of child psychiatrists that the wait often is three months or more for an appointment. Many parents simply can’t wait that long, so they take their kids to a family doctor.

One survey said as much as 70 percent of psychiatric drugs are prescribed by family doctors.

Struggling youngsters lucky enough to get into the mentalhealth system are three times as likely to receive therapy as to receive drugs, Hogan said. Research suggests that children who receive both are more likely to be successful than those who receive one or the other, he said.

Still, 80 percent of troubled youths nationwide fail to receive any help, said Terry Russell, executive director of the Ohio chapter of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill.

‘‘Psychotropic medications for young children should be used only when anticipated benefits outweigh the risks," Russell said. ‘‘But we’d hate to see doctors’ hands tied, because research shows that reaching children with mental illness early significantly improves their long-term prognosis."

Big

profits

in

medications

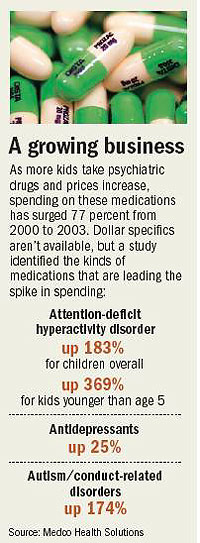

Psychiatric medications are big business.

In 2002, drug companies made $12 billion in profits from antidepressants alone. Those numbers continue to grow, largely because of increasing use on children.

Nationwide, the number of children using psychiatric medications tripled between 1987 and ’99.

But researchers say they don’t have the data to know whether kids are being given risky combinations or dosages, practices experts say occur frequently.

Concerned by these issues, the Ohio departments of Mental Health and Job and Family Services are reviewing two years of Medicaid claims for red flags, including children who are on three or more mental-health drugs.

A consultant hired by the state will begin sending letters next month to physicians whose practices raise concerns, said Margaret Scott, a state pharmacologist.

The consultant, Comprehensive Neuroscience, of White Plains, N.Y., has helped several states, including Florida, where 442 doctors have received such letters.

Private insurance plans don’t report how psychiatric drugs are used by their clients, but because Medicaid is government-run, more information is available.

Nearly 40,000 Ohio children on Medicaid were taking drugs for anxiety, depression, delusions, hyperactivity and violent behavior as of July. For the entire year, the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services paid out about $65.5 million for kids’ mentalhealth drugs.

Concerns also have been raised nationally about the high number of children being medicated in foster care, residential treatment and youth prisons.

In Ohio, 31 percent of children ages 6 to 18 in foster and group homes took mental-health medications in July. And 22 percent of children in detention were on a psychiatric drug as of January. Many were on five or more.

Those who defend the use of medications on these youths note that they often have been victimized.

‘‘A lot of these kids have been beaten, sexually assaulted and emotionally wrung through the wringer," said Laura Moskow Sigal, executive director of the Mental Health Association of Franklin County. ‘‘They have poor self-esteem, feel unloved and suffer from severe psychiatric problems."

Still, parent concerns have prompted other states to respond.

In Texas, Controller Carole Keeton Strayhorn criticized her state’s child-welfare agency for spending as much as $4 million a year on mental-health drugs without enough oversight. She also blasted the agency for giving children drugs to make them docile and so ‘‘doctors and drug companies can make a buck."

Some people think drugs are the cheapest, easiest way to subdue kids for overburdened foster parents and understaffed residential centers. Most pills cost from 2 cents to 17 cents, while child psychiatrists can earn more than $500 per day.

Others think some foster parents want children on drugs so they can get more government money for being classified as a ‘‘treatment" or ‘‘therapeutic" home.

A few say the only way to solve the overmedication problem is to keep children with their parents.

‘‘Only a parent, or another close relative, is likely to put up with difficult behavior from a child, because only family loves that child enough to put up with it," said Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform in Alexandria, Va.

Doctors may know the disease best, but parents generally know their children best, Wexler said.

Even

infants

put

on

pills

Advocates are equally distressed by the high numbers of drugged-up infants. In 1994, 3,000 prescriptions for Prozac were written nationwide for children younger than 1 year old, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Almost all psychiatric prescriptions for toddlers and preschool children are ‘‘off label" — without dosage recommendations and for conditions other than those for which the drugs were created.

Physicians frequently ‘‘dose down" adult medications by adjusting for a child’s weight.

At least 696 Ohio children who were newborn to 3 years old received mental-health drugs through Medicaid in July. Hydroxyzine was prescribed most often, with about three-quarters taking it.

The drug, a long-acting antihistamine, has many uses. It relieves itching caused by allergies, controls vomiting and reduces anxiety. It’s given most often to young children for its sedative effects.

‘‘It’s generally calming, has low side effects and is pretty inexpensive," said Bob Reid, pharmacy program director for Job and Family Services. ‘‘It’s a real bargain."

But Bassuk, the Harvard psychiatrist, says doctors should avoid giving babies, especially those still in diapers, unnecessary medications.

‘‘Sure, there are drugs that make kids sleepy, but what’s the point if they don’t have any medical purposes?" she said.

More than 90 of the children were on another antihistamine, 48 were taking anti-anxiety medication and 28 were prescribed antidepressants, including Paxil, Prozac and Zoloft, which have been found to increase suicidal thoughts and behaviors in some children. Twenty-seven received Valium, and 18 were on antipsychotics.

‘‘It’s troubling," said John Saros, executive director of Franklin County Children Services. ‘‘How do doctors even determine that a 2-year-old is anxious? There’s a reason they call it the terrible twos."

But Martha Hellander, of the Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation in Illinois, says she has seen babies who cry for hours, 2-year-olds who fly into unprovoked rages and 3-yearolds who try to jump out of moving cars.

‘‘The medication is essential for these kids," said Hellander, the group’s research policy director.

Girl’s

death

haunts

parents

Mike and Janet Hall, of Canton, can’t help wondering whether their daughter Stephanie would still be alive if they hadn’t agreed to medicate her. Stephanie died of a heart attack in January 1996, the morning after a doctor doubled her daily dose of Ritalin.

The Halls say Stephanie’s firstgrade teacher pressured them to drug their daughter when she was 6. She remained on medication for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder for years and died in her sleep six days before her 12 th birthday.

‘‘I almost wish she had died 12 hours later at school, on their doorstep," said Mrs. Hall, 40. ‘‘They started this thing by telling us she had to be on medication because she had a problem getting up out of her chair. What do they expect from a 6-year-old?"

The day before she died, Stephanie was ‘‘out of it" in the morning but seemed fine later, Mrs. Hall said.

When her father tried to wake her the next morning, she didn’t move.

‘‘At first, we thought she had the flu," Mrs. Hall said. ‘‘But then I noticed she was cold and blue."

They sued the company that makes Ritalin in January 2000, but the case was thrown out because the statute of limitations had expired.

Today, the Halls warn other parents to research the pros and cons before placing their child on psychiatric medications.

‘‘Stephanie used to tell me, ‘Mom, I’m going to be a firefighter or paramedic because I’m going to save people,’ " Mrs. Hall said. ‘‘But who could save her? No one. She was just a human guinea pig in a failed medical experiment."

epyle@dispatch.com