|

News Special Sections

Advertising Special Sections

Accepting New Patients |

DRUGGED INTO SUBMISSION [ DAY 1 OF 2 ]

Forced medication straitjackets kids

State: Shots needed in emergencies Critics: Children put at risk

Sunday, April 24, 2005

THE COLUMBUS DISPATCH

They are sent away for help. ¶ But when they act out, some troubled children are controlled with potentially dangerous mind-numbing drugs. ¶ No one knows how often residential centers for hard-to-control kids use psychiatric drugs to subdue them. Privacy laws shroud the centers in secrecy. ¶ But a three-month investigation of thousands of state inspection records as well as more than 80 interviews with child-welfare workers, doctors, families, lawyers and industry officials reveal growing concerns that pills and injections, most of them untested on youths, have become a quick fix to stifle troublemakers. ‘‘At its worst, it’s like a scene from the movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest with Nurse Ratched chasing after kids with syringes of psychiatric drugs," said Gayle Channing Tenenbaum, legislative director for the Public Children Services Association of Ohio. At best, it’s a rare problem being addressed through better training, says the Ohio Department of Mental Health. But an advocacy group says Mental Health is making it easier for treatment centers to force powerful drugs on kids without reporting it. Ohio Legal Rights Service, which is leading the charge for change, says the opposite should be done. Mental Health needs to impose far stricter rules to limit the use of medications and hold centers accountable for abuses, it says. Both sides agree that psychiatric drugs can help kids suffering with anxiety, depression or a host of other mental illnesses. The question in these cases is whether medications are being used to treat children or as a chemical straitjacket. Legal Rights, an independent state agency, has examined nearly 500 cases involving chemical restraints during the past five years, including: • A 5-year-old boy who was so doped up that he couldn’t stop batting the air, complaining about imaginary bugs and smacking his lips. A doctor ordered him off all medication. • A 10-year-old boy who was chemically restrained 69 times over 80 days. Doctors prescribed up to six drugs at a time — and never conducted trials to determine which pills worked for what symptoms or disorders. • A 12-year-old girl who was injected six times over nine months with high doses of Thorazine, a powerful sedative that can knock kids out and cause muscle spasms and twitches. She also was physically restrained 31 times by as many as three men, despite a history of being physically and sexually abused. ‘‘It’s scandalous that medications are used to subdue kids for overworked and underpaid staff or as punishment for bad behavior," said Carolyn Knight, the group’s executive director. Children already traumatized by abuse, neglect or mental illness can be hurt further by being forced to take a medication, especially when held down by adrenaline-pumped adults, said Dr. Ellen Bassuk, an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School who has reviewed Ohio cases. ‘‘The mental-health system is a mess," she said. ‘‘Not only are these places giving chemical restraints, but they’re prescribing risky combinations and dosages of drugs that are as dangerous and inhumane." State officials say Ohio law prohibits chemical restraints except in emergencies when a child or worker is in danger. Even then, they’re supposed to be used only after lessforceful options fail. ‘‘It’s been outlawed," said Thomas Wood, chief of licensure and certification for the Department of Mental Health. Critics say the state’s 52 private residential centers often skirt the law by calling the restraints emergency medications or a PRN order — short for a Latin term for giving drugs as needed. ‘‘No one wants to call it a chemical restraint because it is too emotionally charged a term," said Curtis Decker, executive director of the National Association of Protection & Advocacy Systems in Washington. Others say the practice is protected by an unspoken rule: ‘‘Don’t ask, don’t tell." ‘‘It happens underground all the time," said Steve Eidelman, executive director of the ARC of the United States, a national advocacy group for the developmentally and mentally disabled, based in Silver Spring, Md. ‘‘It’s all about what’s easiest for the treatment providers, not what’s good for the kids." In response to that concern, workers at these centers increasingly are being taught ways to prevent power struggles instead of how to physically control children. ‘‘It can be as easy as sitting down with a kid and telling them you hurt my feelings when you called me a name instead of tackling them to the ground," said Bob Bowen, chief executive officer of David Mandt and Associates, a Texas-based training company that Bowen runs from his Canton office.

Injections

as

threats

Concerns about overmedicated kids are being heard nationwide. A children’s psychiatric hospital in Louisville, Ky., was chastised in 2003 for giving drugs to children before they could cause problems — sometimes while still asleep. Kids who refused to take pills were told they would receive a shot of Thorazine. In May 2000, a nonprofit group filed a class-action lawsuit on behalf of 9,000 Tennessee children in large institutions who were given psychiatric drugs and other restraints without proper legal consent. ‘‘There’s no reason to think that Tennessee is an aberration," said Doug Gray, a lawyer for the New Yorkbased, nonprofit Children’s Rights. Defenders say drugs sometimes are needed to control the increasingly unruly, violent youths being sent to the centers. ‘‘They bite, hit, kick and spit," said Penny Wyman, executive director of the Ohio Association of Child Caring Agencies, which represents residential centers. ‘‘They curse, yell and throw furniture. They’re angry and have a lot of issues to work out." Many of the children need the kind of intensive care they’d get at a hospital, but there aren’t enough beds, Wyman said. The state closed most of its mental institutions in the late 1980s and early ’90s but sent little money to community health centers to help with increased caseloads. She said Ohio Legal Rights’ leaders don’t understand the challenges providers face and are on a ‘‘witch hunt," even though treatment centers use psychiatric drugs only as a last resort. Others say they don’t understand the fuss. ‘‘It’s shocking that we focus so much attention on the residential treatment centers, which have fewer than 1,000 beds," said Michael Hogan, executive director of the Ohio Department of Mental Health. The department licenses the centers, four- to 115-bed facilities that together can house 919 children. Thousands of kids flow through the centers in a year, and many more are closed out. Hogan says the biggest danger facing children is depression. There were 168 youth suicides statewide in 2002, the most-recent figures available. ‘‘No case of abuse or neglect is good," he said. ‘‘But it would be wrong for us to ignore the bigger issues, especially as our money gets tighter and tighter." Most treatment centers are doing their best, he said. They’re adding psychiatrists, reducing overall restraint use, training staff members and trying new, positive methods for responding when kids blow up. Hogan’s department thoroughly inspects the centers every two years, or when concerns arise. The centers typically charge $100 to more than $1,000 a day. But most still have few hiring standards and are plagued by high turnover, Knight said. Workers often are fresh out of college and are paid about $7 an hour. The department’s assistant medical director agrees that treatmentcenter workers often are too quick to push drugs because they want calm, obedient children. ‘‘It’s human nature. A lot of adults think children should be seen, not heard," Dr. Patricia Goetz said. ‘‘It doesn’t help that we’re a culture where you can manage everything with a pill."

State

intervenes

Last April, the state ‘‘strongly recommended" that Belmont Pines Hospital, in Youngstown, stop using emergency medications after Goetz uncovered several troubling trends. She reviewed 11 cases in which a total of 27 shots of the powerful drugs Haldol and Thorazine were given to calm angry children. In a letter, Goetz noted that the medications ‘‘have effects that last far longer than required for a patient to regain self-control." Sleepiness can persist for hours or days. And unlike the use of other restraints, such as padded handcuffs or physical holds, there are no limits on how long kids can be drugged, said Laurel Stine, director of federal relations for the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law in Washington. ‘‘It’s just another way to abuse children who have already been victimized," Stine said. Two years earlier, the Department of Mental Health placed Belmont Pines on probation for five months and barred the 45-bed center from admitting more children. The agency took action after Ohio Legal Rights and several Belmont Pines employees complained that the facility gave too many shots of Haldol, Thorazine and Vistaril, an antihistamine used for sedation. One man reported that his son was so drugged up during visits that he couldn’t talk or walk. The boy essentially was being treated as a ‘‘pincushion," said Judy Jackson-Winston, a client-rights officer for the Cuyahoga County Mental Health Board who spoke with the father. Belmont Pines officials said they have stopped using emergency medications and had reduced their use by 86 percent before the state warning. ‘‘We had already made a decision that we were going to reduce, then eliminate their use," said Dr. Phillip Maiden, the group’s medical director. ‘‘The Ohio Department of Mental Health just made us do it a little quicker." Although he regrets that the center was placed on probation, Chief Executive Officer George Perry said, ‘‘There’s no question, we’re better for it."

Multidrug

cocktails

Last summer, Goetz warned about the use of ‘‘drug cocktails" at Pomegranate Health Systems, which runs a center in Byesville in Guernsey County and plans to open a $5 million, 60-bed facility in Franklinton next year. She questioned why five drugs were needed for a 15-year-old with posttraumatic stress disorder and intermittent explosive disorder, which leads to sudden outbursts of violence. ‘‘It is very concerning that this child is on three mood stabilizers — Depakote, Topamax and Trileptal — and two antipsychotic medications — Haldol and Seroquel," Goetz wrote. ‘‘There is no evidence that Topamax or Trileptal decreases aggressive behavior." Few scientific studies have explored the risks associated with using multiple psychiatric drugs. However, experts and researchers agree that drug cocktails increase the likelihood of death or bad side effects. Also, many behaviorial-health drugs agitate children, so workers respond by giving them more medication. Goetz also criticized Pomegranate for using Haldol too often and in high doses, even though the drug can cause potentially fatal side effects, including involuntary muscle contractions, low blood pressure and rapid heartbeat. Pomegranate officials defend their medication practices, saying they treat the most difficult, disturbed children, including those who are victims of violence or attempt suicide. On average, the kids they see have been through 20 foster, group and residential homes, administrator Bob Hall said. Some have had as many as 33 placements. Most have been to a different physician or psychiatrist with each move, and each doctor has prescribed multiple drugs. Complicating matters, the children’s medical records often don’t keep pace with their moves. Pomegranate deals with the problem by creating medical and mentalhealth work-ups within 30 to 45 days of each child’s arrival, Hall said. ‘‘We just received a 71-page package on a kid, and there wasn’t one fact about the kid’s medications in all that paper," Hall said. This type of slip-up proves the system is broken, said Yvette McGee Brown, a former juvenile court judge who is now president of the Center for Child and Family Advocacy at Columbus Children’s Hospital. But it doesn’t take residential centers off the hook. ‘‘They should get those files," she said. ‘‘Anything less is malpractice." While on the bench, McGee Brown frequently called the doctors of children she thought were overmedicated. ‘‘I had a 10-year-old who was so doped up he was walking around like a zombie," she said. ‘‘Sure, he wasn’t creating any problems. But he was barely conscious."

Problems

with

staff

members

Chelsey Kennedy, 15, of Gahanna, never will forget the effect of being given three shots of Haldol one afternoon at Kettering Hospital Youth Services in Dayton. ‘‘I slept for four days and was in a drug-induced fog for a week after finally waking up," she said. ‘‘That’s just wrong!" Chelsey, who has bipolar disorder, admits being combative and mouthy at times. But she said residential staff members often egg on patients. State records reflect that. For instance, the Mental Health Department reprimanded a southern Ohio center in January for creating a ‘‘culture of fear and intimidation." State inspectors said the children at Oak Ridge Treatment Center, near Ironton, complained about being cursed at, called names and insulted by staff members. They also reported being choked, kneed, ‘‘slammed" and put into a ‘‘sleeper" wrestling hold that temporarily cuts off their breathing. Wendy Kennedy, 40, said teens are ‘‘manhandled" at Residential Treatment Centers of Ohio, a South Side facility where her daughter has lived since early March. ‘‘When I went to visit Chelsey recently, one of the girls had a black eye, bloodied nose, busted lip and she couldn’t move her shoulder — all because of a restraint," Kennedy said. ‘‘Using brute force is so wrong." Residential Treatment officials denied using excessive force and said no children have been hurt. ‘‘Franklin County Children Services has found nothing to substantiate any abuse," Chief Executive Officer Jeff Beasley said. But in March 2003, Children Services pulled 11 teens from the center after a worker bruised a girl’s wrist during a restraint. The state also placed Residential Treatment Centers on probation for failing to meet rules. Beasley said the center doesn’t use any emergency medication — ‘‘only drugs ordered by the doctor." However, state mental-health officials cited the facility in August for using a ‘‘medication as a restraint to control behavior." Kennedy is concerned that Chelsey might be on too many and maybe even the wrong medications. Before entering residential care a year ago, Chelsey was on two drugs. She’s now prescribed 14 — 11 psychiatric and three for diabetes. ‘‘The side effects are terrible," said Kennedy, who turned over custody of her daughter to Franklin County Children Services in 2004 to get her mental-health help. ‘‘She has joint pain, reflux and no hormone levels, which have baffled doctors." Chelsey also hasn’t been herself. ‘‘She can be normal one minute and like a small child another," Kennedy said. ‘‘I just don’t understand why they give her so many drugs but no meaningful counseling. It kills me." Gwen Malcuit, 33, of Strasburg in Tuscarawas County, understands Kennedy’s pain. Her 16-year-old son, Nick, was misdiagnosed four times and given more than a dozen medications before doctors concluded he has bipolar disorder. One drug made him sleep 18 hours a day. Another caused him to gain 50 pounds. A third made him fidgety and hyper. ‘‘I really believe the medications impaired his learning," Malcuit said. ‘‘He was angry, out-of-control and thought I had betrayed him." Today, Nick is on one medication and enjoys life as a 10 th-grader. He is doing well in school, has a girlfriend and is looking for a part-time job. ‘‘Look at what happens when you give a child what he really needs: appropriate services in his own home," Malcuit said. She lays part of the blame on the confusing system. For example, four state agencies license residential centers: the departments of Health; Job and Family Services; Mental Health; and Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities. Each has different licensing standards. The Ohio Department of Alcohol and Drug Addiction Services also certifies some programs. ‘‘It’s a maze that leaves families feeling left out," Malcuit said. It doesn’t help that families often relinquish custody of their children to county child-welfare agencies because mental-health care is so expensive. And when they do, they frequently lose the power to make decisions about medications. They’re also afraid to challenge decisions out of fear their children won’t be returned.

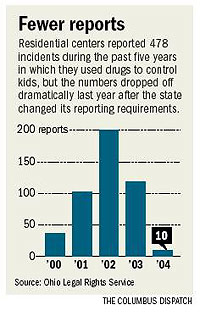

Fewer

reports

Finding out how often treatment centers use drugs to restrain children has become more difficult. In January 2004, the Department of Mental Health stopped requiring treatment centers to fill out incident reports for restraints unless they involved abuse or neglect, or resulted in an attempted suicide, injury or death, Knight said. As a result, the number of reported restraints — both emergency medications and physical holds — dropped from 6,815 in 2003 to 113 last year. Reports of emergency drugs declined from 118 in 2003 to 10 last year. Mental Health officials say providers now have to log the use of restraints daily. The department regularly reviews them and compiles totals every six months. But advocates say the centers aren’t required to note the use of emergency drugs. Meanwhile, state developmental disability officials have toughened their reporting requirements, causing their figures to spike from 12 reported restraints in 2001 to 542 last year. The Department of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities also considers the use of any unapproved psychiatric drug — whether in an emergency or not — a chemical restraint. ‘‘They’re well ahead of the Department of Mental Health on this issue," Knight said. MRDD officials admit they toughened their requirements after a scathing audit by what is now the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in Washington. ‘‘It’s tough asking the painful questions, but if you don’t you’ll never know if a provider is doping a client up with a powerful psychotropic medication just for convenience," Director Kenneth Ritchey said. Since 2000, the department has added 14 people to its investigative unit, created an online registry of caregivers who have abused people with disabilities, and developed a Webbased reporting system for incidents. Ohio Legal Rights would like the Department of Mental Health to be equally vigilant, particularly in requiring treatment centers to report the use of all restraints. Legal Rights points to an incident at Kettering Hospital in Dayton last July in which a 14-year-old girl was restrained — with drugs, handcuffs, other devices and physical force. Eight staff members, a guard and two police officers were involved in the episode, which stretched over ‘‘eight horrendous hours," according to Legal Rights. Details remain sketchy, but the agency’s investigation found: • The teen became agitated and was put in a seclusion room. State officials say she was spitting and threatening staff members. • While in the room, she managed to pull a mattress cover off a bed and zip herself inside. Police were called and put her into handcuffs until she calmed down. Staff members replaced the cuffs with other restraints and kept her tied up for more than seven hours, against state rules. • The girl was given three shots each of Haldol and Cogentin, a medication used to offset potential side effects from the Haldol, including stiffness and tremors. The child-welfare agency responsible for the teen had never consented to the use of Haldol. In the end, the guard filed charges against the girl because he had thrown out his back during the restraint, and she was discharged to another facility. Executive Director David Drawbaugh said Kettering is now committed to a zero-tolerance policy for restraints and seclusion. State mental-health officials said the incident ‘‘raised a lot of concerns" but was not reportable as a ‘‘major unusual incident" under the department’s standards. ‘‘This is the kind of human-rights abuse that occurred in the back wards of psychiatric hospitals 25 years ago," said Laura Wissler, a parent advocate for the Mental Health Association of Summit County. ‘‘If this isn’t reportable, what is?" epyle@dispatch.com

|