|

Nature

Published online: 15

March 2006; | doi:10.1038/440270a

Drug trials: Stacking the deck

Studies of medical literature are confirming what

many suspected — reporters of clinical trials do not always play straight.

Jim Giles talks to those pushing for a fairer deal.

Jim Giles

|

|

|

C.

DARKIN

|

|

They

answer only the questions they want to answer. They ignore evidence that does

not fit with their story. They set up and knock down straw men. Levelled at politicians, such accusations would come as

no surprise. But what if the target were the researchers who test drugs? And

what if the allegations came not from the tabloid press, but from studies

published in prestigious medical journals?

The slurs may

sound over the top, but each is based on hard data. Since 1990, a group of

researchers has met every four years to lay bare the biases that permeate

clinical research. The results make for uncomfortable reading. Although

outright deception is rare, there is now ample evidence to show that our view

of drugs' effectiveness is being subtly distorted. And the motivation, say

the researchers, is financial gain and personal ambition.

"Patients

volunteer for trials, but finances and career motives decide what gets

published," says Peter Gøtzsche, an expert in

clinical trials and director of the Nordic Cochrane Centre in Copenhagen. "This

is ethically indefensible. Change is not easy, but we must get there."

It is a

dramatic conclusion to come from a field of study with no proper name,

staffed by part-time volunteers. Most are journal editors, medical

statisticians or public-health experts, united by fears for the integrity of

clinical trials. For the devotees of 'journalology'

or 'research into research', the literature on clinical trials is their raw

data and patterns of bias are their results.

Some of these

researchers are using their findings to change medical journals and make it

harder for authors to misrepresent results. Others are working on what could

become the biggest reform of clinical-trial reporting for decades: the

creation of a comprehensive international registry of all clinical trials. It

is a powerful idea, which could one day make all trial information public. It

is also an idea that has pitched pharmaceutical companies against advocates

for reform, in a tussle over whether transparency or commercial confidentiality

best serves medical science.

Just say no

One of the

biggest problems with clinical-trial reporting, the suppression of negative

results, shows the importance of such debates. Because clinical researchers

are not obliged to publish their findings, ambiguous or negative results can

languish in filing cabinets, resulting in what Christine Laine,

an editor at the Annals of Internal Medicine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

calls "phantom papers". If that happens, the journal record will

give an over-optimistic impression of the treatments studied, with

consequences for peer reviewers, government regulators and patients.

One alleged

example hit the headlines in 2004. At that time, the antidepressant Paxil (paroxetine), made by

London-based drug giant GlaxoSmithKline, was a popular treatment for

adolescents in the United

States. But doctors have now been warned

off prescribing Paxil to youngsters, after evidence

emerged that it increases the risk of suicidal behaviour.

It was claimed in a court case brought in the United States that

GlaxoSmithKline had suppressed data showing this since 1998. Rick Koenig, a

spokesman for GlaxoSmithKline, says the company thought the charges

unfounded, but agreed to pay $2.5 million to avoid the costs and time of

litigation.

Phantom papers

can be tracked down through trial protocols — the document describing how a

trial will be run and what outcomes will be measured — which have to be

registered with local ethics committees. By matching papers with protocols,

several groups have shown that many trials are completed but not published.

And that, notes Laine, makes it impossible for

journals and health agencies to assess potential drugs. "You never quite

know if other data are out there that would influence your conclusions,"

she says.

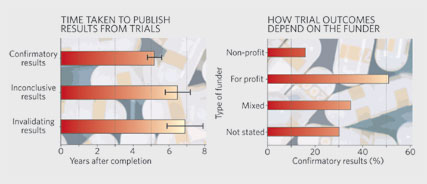

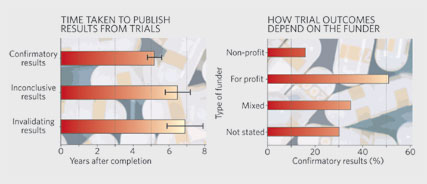

Last year, for

example, a French team showed that only 40% of trials registered with its

country's ethics committees in 1984 had been published by 2002, despite more

than twice as many having been completed1. Crucially, papers with inconclusive

results not only took longer to publish (see graph), they were less likely to

see the light of day at all. Researchers in any field can sit on negative or

inconclusive results. But critics say that clinical researchers carry a

greater ethical burden, as their findings inform decisions about the

licensing of drugs.

Don't

believe the hype

|

|

|

Bitter pill? GlaxoSmithKline denies suppressing data about

antidepressant Paxil's side effects.

J.

RAEDLE/GETTY IMAGES

|

|

Nor

do the problems end when a trial hits an editor's desk. Results from a trial

of the arthritis drug Celebrex (celecoxib)

looked good when they were published in 2000, for example, but less so when

physicians scrutinized the full data set. The original paper, which appeared

in the Journal

of the American Medical Association (JAMA), dismissed fears that Celebrex could cause ulcers. But that was based on data

collected over six months. When other physicians analysed

a full year's worth — which the authors already had at the time of their JAMA submission — they claimed

that Celebrex seemed to cause ulcers just as often

as other treatments2. The original study's authors say that

the later data were too unreliable to be included, but acknowledge that they

could have "avoided confusion" by explaining to editors why they

had omitted them.

This case is

not a one-off. During his PhD at the University of Oxford, UK, epidemiologist

An-Wen Chan looked at the protocols for 122 trials

registered with two Danish ethics committees in 1994–95. More than half of

the outcomes that the protocol said would be measured were missing from the

published paper, he found3. Asked about the missing outcomes, most

authors simply denied the data were ever recorded, despite evidence to the

contrary. And when Chan looked at those missing data, he found that

inconclusive results were significantly more likely to have been left out of

the final publication.

Medical

journals can, however, request such missing data. One idea, adopted by The Lancet three years ago, is to

insist that authors send in a trial protocol when they submit results. That

should help identify whether researchers are reporting all the information

they gathered.

|

|

|

SOURCES:

REF. 1; REF. 4

|

|

But

even with all the data, journal editors face another challenge: hype.

Researchers and sponsors tend to be interested in things that work rather

than those that do not, so authors may subconsciously tweak results and talk

up conclusions. "Researchers are so worried about getting papers

rejected that they put a lot of spin on results to make them seem as exciting

as possible," says Doug Altman, a medical statistician who supervised

Chan at Oxford.

The hype shows

up in a paper's conclusions. In 2003, epidemiologist Bodil

Als-Nielsen and her colleagues at the University of Copenhagen looked at factors that

might influence researchers' conclusions about a drug's efficacy or safety4. Their analysis of 370 trials showed that

the strongest predictor of the authors' conclusions was not the nature of the

data, but the type of sponsor.

|

Patients volunteer for trials, but

finances and career motives decide what gets published. Patients volunteer for trials, but

finances and career motives decide what gets published.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trials

funded by for-profit organizations were significantly more likely to reach a favourable verdict than those sponsored by charities or

governments. Critically, the association was not explained by the papers

having more positive results. In a study under review, Gøtzsche

and his colleagues show that industry-funded meta-analyses — studies that

combine results from several clinical trials of a drug — are similarly prone

to draw positive conclusions that are not supported by the data (see graph).

For many

clinical-trials experts, these funding biases explain all the others. For

each act, be it the suppression of results or the omission of outcomes, there

is a financial motive for the company whose drug is being tested. In many

cases, the company funding the study also employs one or more of the authors.

Given the combination of motive and opportunity, many see drug-company

influence as an inevitably distorting factor.

"When we

see an industry article we get our antennae up," says Steven Goodman, a

medical statistician at Johns

Hopkins University

in Baltimore

and an editor at the Annals of Internal Medicine. "It's not that we

assume the research is done badly. But we have to assume that the company has

done all it can to make its product look as good as possible."

Editorial

control

At JAMA, editors began insisting

last year that all research sponsored by for-profit organizations undergo

independent statistical analysis before acceptance. Cathy DeAngelis,

the journal's editor-in-chief, says JAMA had asked authors to do this for years, but began

requiring it after editors started seeing papers that they thought dishonest.

"People said that for-profit companies would stop sending us

trials," she notes. "Well, guess what? If you look at what we're

publishing you'll see that that's not true."

Still, Goodman

and others caution against blaming everything on industry.

Government-sponsored trials also tend to report positive outcomes5, although the effect is weaker than with

industry studies. And a publication in a big journal can boost authors'

careers as well as company coffers.

|

|

|

JACOB

RIIS

|

|

Others

add that journals must also share the blame. Good peer reviewers and hands-on

editors should, for example, weed out hype. But according to Richard Smith, a

former editor of the BMJ (which was the British Medical Journal) and now head of European

operations for the US

insurer UnitedHealthcare, editors may be biased

towards positive results. In an article published last May, titled

"Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of

pharmaceutical companies", he pointed out that reprints of papers

reporting positive results can generate millions of dollars, and that this

might influence editorial decisions6.

There is

certainly evidence that drug companies attempt to use reprint income as a

lever on journals. The Lancet's Richard Horton has said

that authors sometimes contact him to say that sponsors are likely to buy

large numbers of reprints if their study is published. Horton and other

editors at top journals say they rebuff such threats, but some less well

staffed journals lack policies for separating commercial and editorial

decisions, suggesting that reprint income at least has the potential to

distort decisions.

|

We have to assume that the company

has done all it can to make its product look as good as possible. We have to assume that the company

has done all it can to make its product look as good as possible.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Merrill

Goozner, who tracks pharmaceutical issues at the

Center for Science in the Public Interest, a lobby group in Washington DC,

agrees. "It's a financial conflict of interest, plain and simple,"

he says.

Full

disclosure

Such

accusations make medical editors angry. They deny that commercial pressures

influence peer review, adding that journals have introduced several measures

that have helped to clean up clinical-trial reporting.

One of the

first initiatives, introduced in 1996 and revised in 2001, is the statement

on Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT). A set of guidelines

on how to report a clinical trial, the statement is designed to ensure that

authors present results transparently. It seems to be helping. Since top

journals began insisting that authors follow the guidelines, researchers'

descriptions of their methods, for example how they place subjects in

treatment or control groups, have become more accurate7. Such information aids reviewers'

decisions.

|

|

|

S.

GOODMAN

|

|

Journals

have also endorsed trial registries. By registering all trials when they

begin, researchers will find it harder to suppress outcomes, editors believe.

Several registries already exist, including one run by the US

government. The World Health Organization (WHO) is working on an online

portal that would bind these databases into a single source. And in 2004, the

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors announced its members

would not publish the results of trials that had not been placed in a public

registry.

Clinical-trials

experts welcomed the move, but the industry response was patchy. Last June,

the committee was forced to issue another statement after finding that some

sponsors were being deliberately vague and entering terms such as

'investigational drug' in the field for the drug name. A follow-up study

found the quality of information had improved considerably by last October8.

Despite these

successes, advocates of reform say bigger fights lie ahead. The experts

working on the WHO registry want a list of mandatory entries for trial data,

including the primary outcome. For drug companies this is a step too far,

akin to asking an inventor to publish the description of an invention before

it is patented. Instead, the companies propose depositing such information in

a locked database, to be released when the drug obtains marketing approval.

Going public too early, they say, would deter companies from taking risks on

potential treatments and slow down the generation of new drugs.

Yet for

critics such as Smith, even the WHO portal does not go far enough. Along with

other registry advocates, he would like to see all clinical results, not just

protocols and outcomes, published in public databases.

This proposal

would seem to tackle problems with reporting data and bias. But it would not

be simple. Aside from the commercial concerns of the drugs industry, the

creation of a results database could lead to patients pressurizing doctors

for access to experimental medicines. Health insurers and hospitals might

also change the drugs they use after seeing the raw results, rather than

waiting for peer-reviewed papers.

The debate is

in its infancy. Yet clinical-trials experts are more optimistic than they

have been at many points in the past 15 years. Chan, now working for the WHO

registry team in Geneva,

says the first round of consultations with stakeholders should produce a

policy statement in April. He and others add that although industry will

probably continue to resist, the public attention generated by recent

scandals, and the wealth of data available on the problems, mean that time is

ripe for change.

"I'm not

relying on hope," says Gøtzsche. "But the

results of all trials should be made public, not only those that the sponsor

cares to tell the world about. This is incredibly important."

Jim

Giles is a senior reporter for Nature in London.

Article brought

to you by: Nature

|

References

- Decullier, E. , Lhéritier, V. & Chapuis, F. Br. Med. J. 331, 19–22

(2005). | ISI |

- Hrachovec, J.

B. & Mora, M. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 286, 2398

(2001). | Article | ISI | ChemPort |

- Chan, A.-W. , Hróbjartsson,

A. , Haahr, M. T. , Gøtzsche,

P. C. & Altman, D. G. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 291,

2457–2465 (2004). | Article | ISI | ChemPort |

- Als-Nielsen,

B. , Chen, W. , Gluud, C. & Kjaergard, L. L. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 290,

921–928 (2003). | Article | ISI |

- Dickersin, K.

& Min, Y. I. Online J. Curr. Clin. Trials 2, 50 (1993).

- Smith, R. PLoS

Med. 2, e138 (2005). | Article | PubMed |

- Moher, D. ,

Jones, A. & Lepage, L. J. Am. Med.

Assoc. 285, 1992–1995 (2001). | Article | ISI | ChemPort |

- Zarin, D.

A. , Tse, T. & Ide,

N. C. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 2779–2787

(2005). | Article | PubMed | ISI | ChemPort |

|

|