READ MORE

SIDEBAR: Down the Hatch: The Rothman Report

BLOG POST: Foster Kids on Antipsychotics

That multimillion segment of the antipsychotic market had long been an untapped income source, populated by old-school generics that came with their fair share of side effects.

But now J&J, through its subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals, blew the doors off the market with its risperidone tablet, available in a rainbow of colors and sold under the name Risperdal.

Quite simply, J&J's competitors could suck it. Astra Merck had expected to launch its counterpart nine to 12 months after Risperdal, but intelligence gathered by J&J spooks revealed that the company had voluntarily withdrawn its FDA application. And Eli Lily's competing pill was still years away from approval.

Of course, one of the biggest problems with schizophrenia, besides its soul-crushing dreadfulness and tendency to tear families apart, was that there was only so much of it to go around. Eventually, Janssen would have to expand Risperdal's usage and penetrate new markets. Bipolar. Dementia. Attention-deficit. And, just for the heck of it, stuttering.

Old people and kids were virgin territory; hopefully there were enough psychiatrists out there to find enough things wrong with them that could be treated by a little Risperdal. The problem was, the FDA had denied Janssen's application for pediatric use, which meant that — even though the drug could be prescribed off-label — it couldn't legally be marketed for anything other than schizophrenia in adults.

Janssen got around that prohibition by simply ignoring it and getting down to the business of figuring out how to infiltrate a state's Medicaid formulary and position Risperdal as the preferred drug for a variety of conditions. And the best way to do that was to get state mental health experts and influential doctors at universities to spread the gospel. These were the people Big Pharma calls KOLs — key opinion leaders, experts in their fields, whose casual approach to integrity and love of all-expense-paid junkets in Hawaii helped push product.

With its huge Medicaid population, encompassing prisons, psychiatric hospitals and foster care, Texas was the best state for this. Once a Risperdal-friendly system was installed in Texas, it could be exported to other states.

So Janssen reps went to Texas and trolled for whores. They came out in spades; from the state Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation; from the University of Texas system; from state chapters of national mental health advocacy groups. They all helped Janssen market off-label Risperdal use in children by, in some cases, downplaying the side effects of severe weight gain, diabetes, tremors and the growth of (sometimes lactating) breasts in males.

In 2003, when the whistle was blown and the connection between the experts and the drug companies was revealed, state attorneys general licked their lips in anticipation of filing fraud suits to recover Medicaid costs.

The Texas Attorney General's Office filed its suit in 2004, alleging that Janssen's marketing suppressed information about Risperdal's side effects, manipulated or concealed clinical trial results and created "the false impression that valid and well-supported scientific evidence" supported the prescribing of the drug to children. In its goal to create "noise" in the market, the lawsuit states, Janssen seeded medical journals with ghostwritten studies that were essentially advertisements masquerading as legitimate studies.

But the Attorney General's lawsuit, set for January 9, is about money — about recovering millions the state had spent paying for Risperdal. It is not about the well-being of children in state care, who are still prescribed Risperdal and other antipsychotics. Those kids are other agencies' problems.

So that's how Rachel Harrison, a girl who was born three years after the state Attorney General filed suit, and who wound up in foster care in 2010, found herself swallowing four tablets of risperidone a day, with no clear diagnosis.

Her foster mother had initially complained of Rachel being hyperactive and uncooperative. One doctor thought she might have had a mood disorder. Whatever the case, the easiest thing to do to stabilize this kid in the care of one governmental department was to give her a heavy dosage of a powerful antipsychotic that another department was suing over, and to have taxpayers foot the bill.

Maybe it was the combination of all the other drugs Rachel was on while she was in foster care, but the risperidone didn't cause her to balloon out; she actually lost weight. Her hair became wispy and started falling out. Her eyes retreated into what now looked like a freakishly enormous head. One photo her mother was able to sneak during a visitation — before her cell phone was confiscated — looks like it should be the "before" picture, not the picture of a kid after she's in the state's care.

While there are certainly foster children, and others on Medicaid, who have severe enough conditions to warrant the use of antipsychotics, the remarkable thing is that some of the "key opinion leaders" exposed years ago are still crafting the guidelines for these meds in foster care, and some of the ghostwritten journal articles cited in the Attorney General's lawsuit are still being used to justify the drugs' continued usage.

_____________________

Before any major studies got off the ground, Janssen had already created Risperdal's advertising platform — "One Complete Antipsychotic" — and set its sights on corralling key opinion leaders who could deliver the message.

The company's 1993 Product Market Plan called for penetration of three customer segments: providers (prescribing physicians), KOLs who could "influence the politicians," and payors (government agencies). But first, the company had to, through the use of a comprehensive marketing campaign, "create a need and demand for new first-line antipsychotics" and then persuade everyone that Risperdal was the one drug to meet that need. (Risperdal's patent didn't expire until 2007.)

According to an expert witness report filed in the Texas AG's lawsuit, the push kicked off in earnest in 1995 with the establishment of what would come to be known as the Tri-University Guidelines. Janssen funded the research of three friendly physicians at Duke, Cornell and Columbia, with the understanding that they'd all agree that Risperdal was better than first-wave antipsychotics, according to an expert witness report commissioned by David Rothman, a Columbia University professor and psychologist. [See "Down the Hatch: The Rothman Report."]

To better proselytize their Risperdal-friendly findings — and to better line their pockets from the sale of publications and speaking engagements — the three professors incorporated Expert Knowledge Systems. The J&J-funded entity acted as a "strategic partnership with Janssen," according to a filing in the AG's lawsuit, whose mission was to build brand loyalty. Between grants, educational conferences and dissemination of publications, ESK accepted $942,000 from J&J.

Enter the Texas Medication Algorithm Project, or TMAP.

With the Tri-University Guidelines in place, Janssen now had to find key opinion leaders in order to move Risperdal to the top of the state's preferred-drug list. The idea was to claim Texas, and then export TMAP to as many other states as possible; ultimately, at least 16 states incorporated the project.

According to the Rothman report, some KOLs recruited for the job included Dr. Steven Shon, then the director of the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation; Dr. Lynn Crismon of the University of Texas's College of Pharmacy; Drs. Alexander Miller and John Chiles of UT Health Science Center in San Antonio; and Joe Lovelace, then the head of the Texas chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Janssen, of course, denies the Texas AG's claims. A company spokeswoman said she could not discuss details while the case was pending, but did state in an e-mail that "Janssen is prepared to vigorously defend itself against these claims. We are committed to ethical business practices, and have policies in place to ensure that our products are only promoted for their FDA-approved indication. If questions are raised about adherence to our marketing and promotion policies, we act quickly to investigate the situation and take appropriate disciplinary action."

Prior to TMAP, Medicaid guidelines called for doctors to prescribe generic, conventional antipsychotics; they couldn't touch the much more expensive second-generation drugs, called "atypicals," until two or three conventionals had failed.

The drug companies' hurdles, then, were to come up with solid arguments to move their atypicals to the front of the line, despite their cost and the lack of data showing they were any better than conventionals. They had to persuade KOLs that the exorbitant upfront cost would actually save money in the long run because of the atypicals' relative lack of side effects as compared to conventionals. Of course, there wasn't much unbiased data supporting that.

As Rothman — the Texas AG's expert witness — wrote, "From the very beginning of TMAP, its leaders gave only lip service to conflict of interest considerations, ignoring principles in their search for industry funds...J&J fingerprints were all over the TMAP algorithms."

In one example, Rothman pointed out how in 1996, TMAP positioned both atypicals like Risperdal and the generic conventionals at Stage One, meaning physicians would be able to pick either one as a first choice for patients. But after Dr. Steven Shon and his fellow KOLs accepted $300,000 from J&J and other companies in 1997, conventionals dropped to Stage Four in 1998.

By the time of Janssen's 1999 Tactical Plan, Risperdal was the most prescribed atypical antipsychotic, more than doubling projected sales for each year. (While it was the second-most prescribed atypical, Eli Lilly's Zyprexa actually generated a higher dollar amount because it was more expensive.)

Janssen also desperately wanted to corner the pediatric market. Although Risperdal was already being used off-label to treat children, the company didn't have enough data on pediatric safety and efficacy for FDA approval. When the company sought the pediatric nod in 1996, the FDA responded somewhat incredulously: "You never state for what child or adolescent psychiatric disorders Risperdal would be intended. Indeed, you acknowledge that you have not provided substantial evidence from adequate and well-controlled trials to support any pediatric indications nor developed a rationale to extend the results of studies conducted in adults to children. Your rationale...appears to be simply that, since Risperdal is being used in pediatric patients, this use should be acknowledged some way in labeling."

This was hardly a stumbling block; all Janssen had to do was not tell anyone about this denial and just buy favorable pediatric research and ghostwrite glowing articles.

The go-to man for psychiatric disorders in children was Harvard's Joseph Biederman, a man who would one day explain in a deposition that the only entity with a higher professional ranking than him at Harvard was God. (In 2010, Harvard disciplined Biederman and two other researchers for not disclosing $4.2 million they accepted from pharmaceutical companies between 2000 and 2007. The doctors wrote a letter of apology, explaining that they had "learned a great deal from this painful experience.")

The company built Biederman a research lab, the Johnson & Johnson Center for Pediatric Psychopathology, pledging annual funding of $500,000. According to the Rothman report, a J&J employee explained internally that the purpose of the Center was "to generate and disseminate data supporting the use of risperidone in this patient population." All Biederman had to do was churn out a bunch of our-drug-is-better-than-yours studies under his imprimatur, which would hopefully act like kryptonite on many a skeptical shrink.

It was a bean counter in Pennsylvania's Office of Inspector General, whose job was apparently to rubber-stamp portions of that state's TMAP clone, who blew the whistle.

In an essay, the investigator, Allen Jones, described TMAP thusly: "a Trojan horse embedded with the pharmaceutical industry's newest and most expensive mental health drugs. Through TMAP, the drug industry methodically compromised the decision making of elected and appointed public officials to gain access to captive populations of mentally ill individuals in prisons and state mental health hospitals."

Jones's allegations triggered an investigation into TMAP's reach into the foster care system by the Texas Health and Human Services Commission's Office of Inspector General and the Texas Comptroller's Office.

The latter turned up some weird stuff, like the case of a six-year-old who'd received 60 prescriptions (including antipsychotics and mood stabilizers) in the course of a year. The child was eventually admitted to a hospital emergency room and treated for psychotropic poisoning.

The comptroller's investigators were alarmed by the numbers they crunched for fiscal 2004: 6,913 foster children accounting for 65,469 prescriptions of antipsychotics. The average number of prescriptions for all psychotropic drugs (not just antipsychotics) for the 686 kids aged zero to four was 6.7. The number of Risperdal prescriptions alone was 23,812, which cost the state roughly $4.5 million.

Clearly, there was a problem. And clearly, something as important as vulnerable children treated with medication whose safety and efficacy were in question demanded a serious, thoughtful response.

What the children got were a set of guidelines, the Psychotropic Medication Utilization Parameters for Foster Children, developed in 2005 by some of the same people already outed as industry shills.

_____________________

The parameters were overseen by some of the most important acronyms in state government: the Department of Family and Protective Services, the Department of State Health Services, and the Health and Human Services Commission.

They've been updated periodically, most recently in December 2010.

The acronyms involved have touted the parameters as being responsible for lowering the percentage of antipsychotics used in foster care. But among the more astounding things is that the parameters cite some of the same journal articles that the Rothman report exposed as ghostwritten and that two respected psychiatrists the Texas AG hired as expert witnesses in the Janssen lawsuit are critical of the parameters.

Dr. Robert Rosenheck, a professor of psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine, wrote that "the review seems further unduly biased in favor of risperidone in particular."

The other expert witness, Dr. Bruce Perry, senior fellow of Houston's ChildTrauma Academy, and adjunct professor of psychiatry at Northwestern University, wrote that the group behind the parameters "should provide full disclosure regarding their current and past relationships with industry, including direct funds for consultation, speaking, and indirect funds to support 'education' or 'research.' This should also include the professional groups who are claiming to endorse this."

Besides that lack of financial disclosure, the parameters suffer from the inclusion of ghostwritten journal articles, something that a rash of lawsuits against drugmakers have shown is more common than originally thought.

In 2009, the Journal of the American Medical Association conducted a survey on the rates of ghostwriting in 630 articles published in six medical journals in 2008. The Journal published ghostwritten articles at a rate of 7.9 percent; the New England Journal of Medicine's rate was 10.9 percent.

As described in the AG's expert witness report, a company called Excerpta Medica was hired to draft some of Janssen's Risperdal articles.

In 2003, according to Rothman, Excerpta Medica issued "Risperidone Publication Program Status Reports," indicating that 30 of the 145 articles to be published had authors listed as "to be determined."

Rothman also examined what he considered a signature ghostwritten piece meant to boost Risperdal's pediatric profile; the study is included in the 2010 parameters.

Rothman cited a barrage of e-mails between Excerpta Medica and J&J in crafting the article. At one point, an Excerpta Medica employee wrote, "It would be very helpful to receive some guidance in relation to the flow, format and subject in this paper and whether you think this is too marketing oriented or not, in order to prepare a next draft. Besides that we would like [to] have some suggestions for external authors on this paper. Maybe [a] U.S. and a European KOL? Your input will be much appreciated.'"

The article eventually appeared in a 2007 volume of the European Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. For a lead author, J&J scored a heavy hitter: Dr. Peter Jensen, former associate director of child and adolescent research at the National Institute of Mental Health, and the founding director of the Center for the Advancement of Children's Mental Health at Columbia University. Now with the Mayo Clinic, Jensen declined to comment for this story.

While the article noted funding from J&J, as well as the fact that three of the authors were J&J employees, there was no conflict of interest statement and no disclosure of Excerpta Medica's involvement, Rothman wrote.

For another article, meant to tout Risperdal as a good treatment for acute mania, J&J and Excerpta Medica staffers met to hammer out the niggling details, like whose name would go on it. The "Publication kickoff meeting" notes state: "Lengthy discussion ensued around the importance of authorship from internal and external perspectives, and from clinical vs. commercial perspectives."

Perhaps a more malignant form of ghostwriting involved an article touting Risperdal's efficacy in children with below-average IQ: After reviewing Excerpta Medica's various drafts of the manuscript, Rothman wrote, "J&J conducted a separate review of the manuscript and made changes that would put Risperdal in a better light...In the abstract, for example, Pandina [a J&J employee] changed 'no negative effects' to 'positive effects.'"

Dr. Howard Brody, who heads the Institute for Medical Humanities at the University of Texas Medical Branch, has concerns about ghostwriting's contamination of medical literature. Brody studies conflicts of interest, which he explored in his 2007 book Hooked: Ethics, the Medical Profession, and the Pharmaceutical Industry.

In looking at the rise of atypical antipsychotics, Brody says, two major questions come to light: Are they overprescribed, and "the question of the impact this has on what's in the medical literature and whether...we're distorting the scientific base of medicine by ghostwritten articles, and articles that are deliberately spun in order to sell drugs rather than to present the dispassionate, scientific information. And of course, you could do a lot more damage with the latter than you can with just one physician prescribing, you know, for one group of patients."

When asked about the inclusion of ghostwritten articles in the 2010 parameters for antipsychotics in foster care, DFPS spokesman Patrick Crimmons explained in an e-mail, "We don't agree with that characterization — that it is a 'ghostwriting company.' It is a publishing company."

_____________________

In 2009, State Rep. Sylvester Turner co-authored a bill calling for the prior authorization of any antipsychotic prescribed to children under age 11 who are enrolled in Medicaid.

The bill was DOA; a substitute measure calling for the Health and Human Services Commission to study the safety and appropriateness of antipsychotics for Medicaid children under 16 was passed in its place.

While it may be easy to criticize the acronym agencies for continuing to use potentially compromised doctors and data, it's another thing to be in the foster care trenches, treating children who can be in great physiological pain.

Just as the Texas Comptroller cherrypicked some truly outrageous instances of overmedication and departmental neglect in her report on antipsychotics in foster care, the commission found severe cases where nothing but antipsychotics seemed to work.

Take the case of a 20-month-old male whose mother reportedly used multiple drugs during pregnancy: He wouldn't stop banging his head and biting himself, had "an inability to soothe himself, and increased agitation with touch, making feeding, bathing, and diaper changes extremely difficult."

He couldn't be held, "as this will trigger crying episodes and repeated head banging and biting." Ultimately, a neurologist put him on a low dose of risperidone, which seemed to reduce the symptoms.

In perhaps a less compelling case, risperidone came to the rescue when a hyperactive and disruptive three-year-old girl didn't respond well to her daycare teacher sprinkling Dexedrine on her pudding. After risperidone, the girl "is now able to sit in groups," whereas before she would try to escape the classroom. "Several times she has managed to get out of the daycare, and was found outside near the street." (It is unclear whether the state commissioned another study to examine the mystery behind that particular daycare's apparently nonfunctioning doors or lack of a playground fence.)

Some physicians and mental health advocates saw Turner's bill as a medically risky governmental intrusion, another bureaucratic layer that might delay much-needed help.

Generally, the commission's study appears to have at least attempted a balanced, reasonable approach to examining the issue, with a goal of using the best science possible to determine if and when to use these kinds of drugs on such a young population.

That's why it's all the more frustrating that the study cites ghostwritten journal articles in its appendix, and holds up the conflict-of-interest-plagued parameters as an example of evidence-based policy. It's almost as if, six years after the Texas AG sued Janssen, the commission either wasn't aware of the evidence amassed in that lawsuit, or simply didn't care. (Unlike the parameters, the commission study at least attempted to identify the journal articles that were funded by drug companies.)

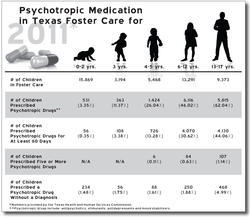

The commission found that, since 2005, "physicians have prescribed fewer psychoactive medications" to children in foster care. The study claimed that, from 2004 to 2009, "the percentage of youth in foster care receiving a psychoactive medication for 60 or more days decreased by more than a third, from 29.9 percent to 19.7 percent."

Recognizing a shortage of mental health experts in parts of the state, the commission called for the consideration of "consultation, including via telemedicine, for non-psychiatrists serving Medicaid youth with mental health disorders," as well as the consideration of wider integration of psychosocial services.

Importantly, but unsurprisingly, the commission distinguished three areas "in which there is little to no high-quality evidence on the use of antipsychotics": The use of multiple concurrent antipsychotic medications in youth; the use of any antipsychotic in children under three (with only "minimal evidence" for use in kids ages three to five); and the long-term effects (greater than three years) of any of the antipsychotics.

In her comments to a draft of the study, Dr. Regina Cavanaugh, president of the Texas Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, saw Turner's proposal as just another barrier to treatment: "As the new president of TSCAP, it is with a sad heart that I tell you that I no longer provide care to foster care children," she wrote. "...I gave up seeing foster care children within 2 years, as I was unable to provide the quality of care I believed was necessary. Caseworkers withheld consent for antidepressants for children who were sexually abused and suffering with depression and PTSD, and not responding to months of therapy...The time needed to do prior authorizations, and the growing restrictive formulary were not conducive in my practice setting."

Dr. Debra Atkisson Kowalski, chair of the Texas Society of Psychiatric Physicians' Child and Adolescent Committee, wrote that "increasing administrative burdens upon physicians to provide care could directly result in less care being available."

Upon presenting his measure to the House Public Health Committee, Turner said, "This bill does not deny any medication to any kid...We are not saying a blanket 'no'" to any medication. He called it "not a red light, just a cautionary light."

Picking up on vehicle-related metaphors, Federation of Texas Psychiatry lobbyist Steve Bresnen told the Public Health Committee that he was part of the original legislation that spawned the parameters: "We built a car. We didn't throw a wrench into the works...I'm afraid this bill will throw a wrench into the works."

Bresnen felt great affinity for the movement behind the parameters, claiming, "I wrote that legislation spontaneously, sitting at my desk." He took great umbrage at a previous speaker, part of the Church of Scientology's "Citizens Commission on Human Rights," who supported Turner's measure, perhaps in no small part because Scientology abhors psychiatry and its attendant medications.

"I'm not going to have the people who wrote the 2005 legislation slimed without responding," Bresnen said, pointing out the speaker's Scientology ties.

Also on the record as opposing the bill were members of the Texas Pediatric Society, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, and Mental Health America of Texas, the last two organizations heavily funded by drug companies.

On hand to testify, should any of the legislators on the committee have questions about the Texas AG's lawsuit, and its uncovering of extensive conflicts of interest and ghostwriting, was Cynthia O'Keefe, deputy chief of the office's Civil Medicaid Fraud division. Strangely, there were no questions.

Dr. George Santos, of the Harris County Hospital District's management board, and a member of the Texas Society of Psychiatric Physicians, also opposed the bill, saying he was "always a little bit nervous about legislative intrusions into doctor-patient relationships."

Santos added that the state's mental health experts were also keeping abreast of "the peer-review journal articles" in order to continue providing the best care for children in Medicaid.

As Santos wrapped up, committee member Garnet Coleman thanked him and said, "I trust that you're going to continue, as you always have, to protect the integrity of the practice of psychiatry."

"You wouldn't let me do anything else," Santos said.

_____________________

"Integrity" probably wouldn't be the first adjective that Rachel Harrison's family would use to describe what happened to her.

Rachel appears to have wound up in foster care after her father had a falling-out with an extended family member, who subsequently called CPS with an allegation that Rachel's mother had tested positive for marijuana while she was pregnant. While there were no signs of abuse or neglect, Rachel's parents at one point tested positive for cocaine. This was enough to remove Rachel from the home.

After Harris County District Court Associate Judge Stephen Newhouse found there was absolutely no evidence of abuse or neglect, and after expressing his bewilderment over why she was put on an antipsychotic in the first place, he returned Rachel to her family last May, 11 months after the state removed her.

Although the judge ordered DFPS to turn over Rachel's medical records to her family, DFPS has maintained they are departmental property and have not followed the judge's orders. In the end, Rachel's parents got the documents from the County Attorney. To this day, they say, they don't know the extent of the drugs she may have been prescribed. (Rachel's story was first reported by KRIV investigative reporter Randy Wallace, whose reports may have had a lot to do with why CPS ultimately changed its mind about terminating parental rights.)

The safety apparatus suggested within the parameters somehow failed to notice that Rachel was prescribed twice the state's recommended dosage of risperidone, without even having a clear diagnosis. However, it may not have been a big deal, because the notes of one of Rachel's doctor's reflect that the medication risks were "discussed with patient," that the patient was "counseled on recognizing medication side effects and adverse reactions" and that the patient "voiced understanding."

In the beginning, David and Christina Harrison say, they weren't even told their daughter was taking risperidone. And an e-mail one of Rachel's CPS caseworkers accidentally copied them on explains how the agency didn't want to disclose the extent of her medication: "He asked why was he not notified about Rachel being on medicine," the woman wrote. "I had another call come in and I stated to hold. When I retrieved the call I stated to him I was uncomfortable and wanted to speak with him in the presence of my attorney only."

Rachel's parents say that she was fatigued during visitations and alternated between vomiting and drooling. They also say she would mimic her various doctors by scribbling on paper and handing it over, as if it were a prescription.

"Physically, she came around quickly," David says of Rachel's return. "You know, four-year-olds, they're built like steel. They bounce back — physically — very well. Mentally, socially, she wasn't the same Rachel." He says it took about five months before she started "being Rachel again." ("Being Rachel" includes riding her pink bicycle, begging her grandmother for just one more popsicle and ordering any visitor to the home to listen to her strum endlessly on a guitar.)

During that time, which the parents refer to as Rachel's detox or rehab period, Rachel would sometimes grow anxious, and her mother says she eventually turned to the power of the placebo: She gave Rachel SweeTarts that were the same color as the risperidone.

While Rachel was gone, her parents sat through court-ordered parenting classes. Considering the circumstances, Christina Harrison's class notes are strangely funny. There's one section, for example, on "how to deal with kids on drugs." Another lesson concerned "preventing problem behavior" and "correcting misbehavior." These involved things like explaining positive and negative consequences; telling a child what to do instead of what not to do; and showing empathy.

Oddly, nowhere in the lesson does it say: Give the child an antipsychotic.