Psychiatrist tries a different approach with dementia patients

Last Modified: Saturday, January 1, 2011 at 9:34 p.m.

The pixie-like patient in a pink dress and a long, flirty strand of pearls lights up as visitors approach, and scoots her wheelchair along the corridor to give them her standard greeting.

Click to enlarge

"Okinawa! Saipan! Iwo Jima! Rome!" she chirps, alluding to the military career that took her around the world -- long before dementia brought her here, to the Garden Memory Unit at Pines of Sarasota.

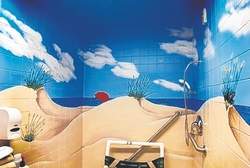

She tags along as the visitors inspect a shower room that has been freshly painted with an expansive scene of Gulf-front sand and sky.

"Isn't that the most beautiful thing you've ever seen?" she asks them. "I love it in there!"

Dementia patients can get anxious to the point of violence while bathing, and this cheery beach mural is one of many small innovations that have lifted moods here in recent months. Under the direction of psychiatrist Dr. Miguel Rivera, caregivers at the Pines have deployed such simple spa comforts as music, massage and calming colors to help reduce agitation. As a result, dosages of antipsychotic medications have dropped to less than half the state average for this most challenging patient population.

Rivera, a gentle, sweet-spoken native of Puerto Rico who completed his psychiatric residency at the University of South Florida in 2001, stresses that none of these therapeutic tactics are his own invention.

"These were not things they taught us in our residency program, but I didn't create them, either," he says. "I'm more the person that maybe has the credentials to bring this to people, and people will tend to believe me because I have this M.D. behind my name."

But Pam Polowski, the Alzheimer's Association program specialist for Sarasota County, says Rivera works a kind of magic that is rare in this field.

"One of the things that is really important to know is that we can't drag our dementia patients into our world," Polowski says. "We have to go to their world and join them on that journey. And he gets that."

Dementia is a loss of brain function that cripples memory, emotions and behavior. Medicare payments for services to dementia patients are expected to total $172 billion in 2010. So low-cost interventions such as Rivera's could save tax dollars.

In a light-filled common room at the Pines, activities director Shirley Riesz is using karaoke to help 20 or so residents power through the normally trying hours before suppertime. Dementia patients' circadian rhythms can make them prone to "sundowning," Rivera explains, when they "begin to pace, get aggressive, want to go home and set off alarms" on the unit's doors to the outside world.

A music therapy session at any long-term care facility can be a dreary, halfhearted ritual. But here, the atmosphere is alive. As "High Hopes" plays, Riesz holds the microphone for a man who sings out strongly, "Whoops, there goes another rubber tree plant!"

Even those not joining in are attentive and mostly smiling. Several wave at Rivera, and he waves delightedly back.

"They don't know I'm a doctor," he said, indicating his casual, golf-style shirt. "They just think I'm this friendly guy who comes around a lot."

Through research and trial and error, Rivera has discovered that what he calls "courting music" -- from the days when his patients were young and in love -- evokes the most dramatic responses. He explains that the vivid connection between a particular song and a potent emotion reflects "things that the mind doesn't really know. If you are really able to concentrate and visualize through music, you get transported and the body responds."

Rivera tells the story of Ann, who moved to the memory unit from the assisted-living section of the Pines after a stroke. Unable to speak, she was despondent and withdrawn.

"I had the intuition that what we really needed to do was to start her on a singing program," he recalls. "We started to notice early on that she was able to sing words and phrases that she was not able to speak. Little by little, it started to spill into her day. She started saying 'OK' or 'yes' or 'no.' We never knew that she liked coffee until the other day, when she told Shirley, 'I love coffee.' So now she gets to enjoy her coffee."

And there is Grace, the patient so upset by the bathing process that she was giving her attendant bruises.

"This is a Monday ritual without fail," Riesz wrote in a recent e-mail message to Pines education director Joann Westbrook. "But today there was NO screaming, just laughing, dancing and singing."

The song that did the trick, according to certified nurse assistant Valrie Miller, was "Will You Love Me Tomorrow?" After the first nonviolent bath time, Miller says, Grace asked her, "Will you love me today?"

Thanks to a small grant that paid for iPods and "courting music"; waterproof plastic iPod holders made by Rivera's neighbor, a retired engineer; and those calming beach scenes painted by Westbrook's husband, K.C. Higgins, the Pines found a way to do for Grace what the strongest pharmaceuticals could not.

"What is ironic," Riesz added, was that "her daughter gave me a preferred music CD and it has no connection or relation to the genre she was enjoying. Let that be a lesson to us: Make up your preferred playlist of music now, because someday your children may do it for you."

Rivera, who works as a mental health medical director for seven long-term care facilities in Sarasota, did not plan any of this.

He came to Sarasota in 2001 with what he now calls the "grandiose" idea of running an alternative, yoga-based medical practice that would "teach people how to change their lives." The business failed.

"Right around the same time that this is disappearing," he says, "I get a call from Bruce Robinson, the chief of geriatrics at Sarasota Memorial. And he said, 'Hey, I heard you were in Sarasota; would you mind doing some nursing home consultations for me?' They say in Spanish, when you're born to be a hammer, it rains nails from the skies."

Robinson says finding trained psychiatrists to take on this work is a struggle.

"There's a desperate need for more mental health care in long-term facilities," he says. "It's a shame there aren't more doctors like Miguel. He's there. He answers his phone."

Rivera took to his mission right away. But he was frustrated that his only option for helping distraught patients was to increase their medications.

"I remember so many times walking through that old west hallway at the Pines" before the building was remodeled, he says. "After the first few years of me working there and seeing how people were overmedicated, and boredom was so prevailing, I remember -- and I feel it right now -- just walking down that hall, and praying, saying, 'Please, God, show me a way.' "

It was Rivera's wife, Natasha, he says, who put him on a path to exploring alternatives to drugs. Both practitioners of TriYoga, they met in 2007 on a spiritual trip to India. By the end of the three-week stay, they were married. A year later, she joined him in Sarasota from her native Russia. And almost immediately, Rivera says, she changed the way he was doing his job.

"All of a sudden there is this fresh pair of eyes that is asking all these questions," he says. "'What is Alzheimer's disease? Why do people get it?' It made me look at things; it took me out of that automatic mode."

Rivera soon found research on the use of music, massage and other therapies on dementia patients. His reading also led to the use of daily affirmations by Pines staffers, who tell the patients, "You are safe; you are loved; you are happy." The result, says Westbrook of the Pines, was "this whole beautiful circle he has created here that has changed that unit."

Robinson views Rivera's work from a more scientific standpoint, and applauds the fact that out of some 40 patients in the Pines memory unit, only eight are taking antipsychotic drugs.

"I am happy to have them report that," he says. "Since the only evidence we have for the effects of antipsychotics is that they kill people, anything that can reduce that is a good thing.

"The life of an old person with dementia can be very meager: Where's the fun?" Robinson adds. "The idea of having something positive in your life, like massage -- all those things have an evident face validity."

Now Rivera is on a new mission: studying links between lifestyle and diet and the onset of dementia, hoping to intervene before people ever need his services.

He maintains that the current epidemics of diabetes and heart disease have a correlation with dementia.

"Alzheimer's is the brain equivalent of that process," he says. "It's chronic inflammation. What is happening in the body is also happening in the brain."

This story appeared in print on page A1