© 2022 MJH Life Sciences™ and Psychiatric Times. All rights reserved.

A lawyer weighs in on pharmaceutical corruption and involuntary psychiatric care.

BillionPhotos.com/AdobeStock

CONVERSATIONS IN CRITICAL PSYCHIATRY

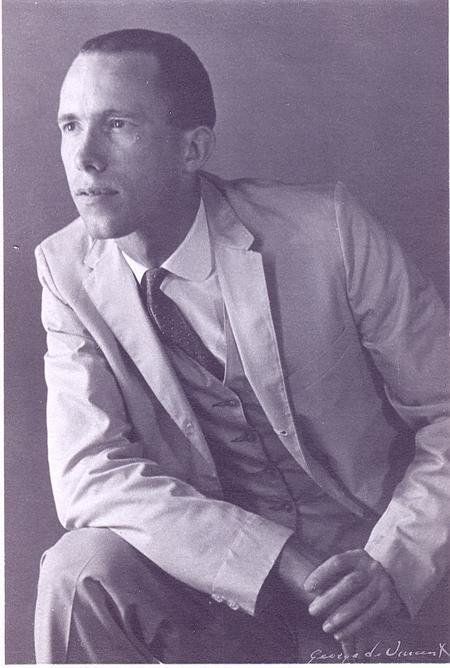

James Barry “Jim” Gottstein is an Alaska-based lawyer and a well-known advocate for the legal rights of individuals with serious mental illness. He graduated as a lawyer from Harvard Law School in 1978. In 1982, he experienced a psychotic break due to sleep deprivation and was introduced firsthand to the mental illness system. This encounter led him to legal representation and other advocacy for individuals diagnosed with mental illness. Gottstein opened his own law office in 1985, generally focused on business matters, and is now mostly retired from the private practice of law. He cofounded the Law Project for Psychiatric Rights (PsychRights) in 2002 and currently serves as its president. Gottstein is the author of The Zyprexa Papers (Samizdat, 2021).

The Zyprexa Papers is a fascinating story of how Gottstein obtained and shared confidential documents showing that Eli Lily executives had knowingly concealed data related to metabolic risks of Zyprexa including diabetes, downplayed risks in published data, and illegally promoted off-label use in children and the elderly. These documents led to a series of front-page stories by The New York Times in 2006,1 and Gottstein became the target of the ire of Eli Lilly’s army of lawyers. Gottstein provides a detailed account of the events in the book.

While it is no surprise, it is still disturbing to see how pharmaceutical companies engage in blatantly unethical practices and how they employ the legal shenanigans to avoid any meaningful accountability, and how we, as a society, repeatedly allow that to happen. It takes great courage—one might even say recklessness—on the part of lawyers and activists such as Gottstein to expose such wrongdoing at great personal risk. As David Healy has commented, “… everything we know about what pharma gets up to comes from legal actions in the US and a handful of lawyers like Gottstein.”2 Half of the book is about Bill Bigley, whose psychiatric commitment and forced medication case enabled Gottstein (his lawyer) to subpoena the Zyprexa Papers and whose rights he defended vigorously, going all the way to the Alaska Supreme Court and resulting in landmark decisions. I left the book with a renewed sense of moral disgust directed at pharmaceutical corruption, a renewed sense of alarm at their pervasive influence and lack of meaningful public accountability, and a renewed appreciation for the legal rights of individuals with mental illness.

Aftab: Tell us more about your background and how you got involved in psychiatric legal advocacy.

Gottstein: In 1982, at age 29, after taking on too much, I got sleep deprived, became psychotic, and was hauled to the hospital in a straitjacket. Before that happened, I had no idea my mind could become unreliable. It was a complete shock. Those that believed I was a lawyer told me I would never do that again, and when I told them I had gone to Harvard Law School, that confirmed I was delusional. I was told I would have to be on psychiatric drugs for the rest of my life and the best I could hope for was to minimize my time locked up in psych wards. Luckily, my mother referred me to a wonderful psychiatrist—Robert Alberts, MD—who told me anyone who gets sleep deprived enough will become psychotic and I could learn how to prevent that from happening. In other words, I escaped having my career changed from being a lawyer to that of a mental patient. I felt lucky in so many ways and resolved to try and help others not so lucky.

There are a number of themes, as it were, in my book, The Zyprexa Papers, and one of them is to subtly bust the myth that people who get diagnosed with serious mental illness cannot recover. I do this by briefly describing a number of people who recovered after being diagnosed with serious mental illnesses and were involved in the events surrounding the release of the Zyprexa Papers.

Aftab: It is inexcusable that you and countless others have been told such things. As an early-career psychiatrist who finished training not too long ago, my perception is that there has been progress in this regard, although practice is far from optimal. I think the development of first-episode psychosis specialty programs and the recovery movement have really emphasized the diverse trajectories of psychosis in treatment approaches, and many prominent psychiatrists (such as Robin Murray, MD; Jim van Os, MD, PhD, MRCPsych; and Patrick McGorry, MD, FRCP, FRANZCP) have questioned the validity of the notion of schizophrenia and the prognostic pessimism that has historically surrounded it. We have examples of researchers with lived experience and their perspectives on recovery, such as Nev Jones, PhD, which inform our thinking. It is worth noting though that the issues that surround involuntary care are distinct from concerns pertaining to erroneously misleading narratives about recovery surrounding psychosis. The 2 are linked in your experience, but a different psychiatrist in an alternative history may very well have given you a more hopeful message during your involuntary hospitalization and may have facilitated your return to work.

Gottstein: My sense is, in the main, the "Abandon All Hope Ye Who Enter Here" message has not changed much—if at all—in the trenches.

There are some encouraging developments, and I hope they will gain traction. Personally, I am spearheading the follow-up activities for MindFreedom International and Rethinking Psychiatry to the International Peer Respite Soteria Summit held virtually on the 5 Sundays of last October. We are actively working on helping people open these types of programs and provide support for ones that are currently operating. There is huge interest around the world, with over 750 people participating from 40 countries. It may be good timing because more and more people are coming to the conclusion that we need to do things differently. On the other hand, in the United States, the scapegoating of people thought to be mentally ill is the only approach everyone can agree on as a response to mass shootings in the US, and seems likely to lead to more psychiatric confinement and psychiatric drugs, often coerced.

Aftab: What have you learned over the course of your legal career about the ways in which pharmaceutical companies misrepresent, misreport, or mis-advertise findings from clinical trials? How can we, as a society, safeguard against this, and how can they be held accountable?

Gottstein: The ways pharmaceutical companies misrepresent, misreport, and mis-advertise clinical trials are legion. I think the most important thing to keep in mind is, in order to gain regulatory approval and promote sales, clinical trials are designed to inflate benefits and hide the harms, rather than be a neutral evaluation. One of the ways they do this is through miscoding adverse events, such as suicide attempts being coded as lability. Another is by assuming adverse events are not related to the drug. Pharmaceutical companies can get away by not looking for unanticipated adverse events. Sometimes they deliberately conceal or minimize adverse effects, as they did in the case of Zyprexa. They also rig the benefit side. As I write in The Zyprexa Papers, in its clinical trials, in order to make Zyprexa look good in comparison, the so-called placebo group were people who had been abruptly withdrawn from Haldol, which is known to exacerbate or even cause severe psychiatric symptoms, and then the introduction of Zyprexa in the trial relieves some of those withdrawal symptoms, which manifests as clinical improvement compared to placebo. They went even further. While most people abruptly withdrawn from Haldol experience withdrawal psychiatric symptoms, some people do quite well, and they threw them out of the study. They hijacked the term “placebo washout” to describe this.

There are plenty of things that could be done about this, but the pharmaceutical juggernaut is difficult to stop, especially politically. For example, David Healy, MD, is on a mission to make the trial data available for review at the participant level, including being able to interview the participants. He makes the point it is outrageous the drug companies claim these data are trade secrets when volunteers risk harm for the benefit of society.

The most practical—and a very effective thing that could be done, in my view—is for prescribers to be appropriately skeptical of drug company claims for their latest and greatest drugs. The reality is the newer drugs are, in most instances, neither more effective nor safer than the older drugs. Often the opposite is true on both scores. It is amazing to me people prescribe the “latest and greatest” new drug, typically at much greater cost, based on the word of companies that are well-known to have lied to the professionals and the public. The true benefit of the newer drugs is monopoly prices can be charged because they are still on patent. As a general matter, the true benefits and harms of a drug are not known until it is off patent.

Aftab: Since The New York Times published the story on the Zyprexa Papers in 2006, there have been numerous other scandals involving pharmaceutical companies. There is much greater awareness now of the criminal role played by Purdue Pharma in creating the opioid crisis in the US. The links between the FDA and pharma continue to be a source of concern, as evident recently in the controversy surrounding the approval of aducanumab despite a manifest lack of efficacy. Do you see any reason to think that we, as a society, are any safer and wiser in our dealing with pharma than we were in 2006?

Gottstein: No.

You want me to say more? If anything, I would say it is worse. For a brief period of time after the release of the Zyprexa Papers and the accompanying New York Times articles, lawyers representing pharmaceutical victims were less willing to agree to keep the harms of drugs secret in order to achieve a settlement, but my sense is things have gone back to normal where the harms of drugs discovered during litigation are kept secret as a condition of settlement. The courts are supposed to look out for the public interest, but they, as well as the parties, are only interested in settlement. If keeping the harms secret is what it takes for the victims to get some (usually inadequate) compensation, the lawyers to get (usually exorbitant) legal fees, and to get the case off the court's docket—so be it.

The corruption of the medical literature has gotten to the point of absurdity, with a large percentage of medical journal articles ghost-written by the drug companies, the prominent “authors” being paid by the drug companies to put their name on the articles not even allowed access to the data.

Aftab: I am somewhat heartened by the developments in psychological sciences, where many of the top journals have embraced the ideals of open science and require sharing of pertinent data. Psychology has also matured from the replication crisis. Medical journals are still behind, unfortunately, when it comes to the goals of open science, although they have taken some half-measures against ghost-writing and have improved their requirements with regards to preregistration of trials, specifying primary outcomes, and spinning of results, etc. It remains the case that many academic authors who put their names on pharma-conducted RCTs do not have direct access to data and depend on whatever analyses the pharma statisticians provide. It is disappointing that litigation leading to settlements is not serving public interest by keeping harms secret. All of this speaks to the lack of systemic safeguards—both medical and legal—and resultantly, there is a disproportionate responsibility on clinicians and patients to maintain a critical attitude.

Your advocacy through the Law Project for Psychiatric Rights (aka PsychRights) has substantially altered the legal landscape in Alaska with regards to involuntary psychiatric commitment and involuntary use of medications via a series of landmark Alaska Supreme Court rulings. Can you give us an overview of what these rulings were about?

Gottstein: PsychRights has won 5 Alaska Supreme Court cases, 3 of them on constitutional grounds. For involuntary commitment, the Alaska statute allowed someone to be psychiatrically confined as gravely disabled if their previous ability to function in the community would otherwise deteriorate. In the 2007 Wetherhorn case, the Alaska Supreme Court held this unconstitutional unless construed to mean the person is “unable to survive safely in freedom.” In other words, the level of disability has to be life-threatening to justify the “massive curtailment of liberty” locking someone up is.

As to court-ordered administration of psychiatric drugs, the Alaska statute said if the person is found to be incompetent to decline the drugs, the hospital is allowed to force into the person any drugs, at any doses the hospital wants. In the 2006 Myers case, the Alaska Supreme Court held this was unconstitutional with the hospital having to also prove by clear and convincing evidence the forced administration of medication is in the person's best interest and there is no less intrusive alternative available. This was expanded upon in the 2009 Bigley case, with the Alaska Supreme Court ruling the state has to provide a constitutionally required less intrusive alternative to forced medication or discharge the patient. The continued viability of this is questionable, however, as a result of a more recent involuntary commitment decision holding the less restrictive alternative to involuntary commitment has to actually exist and be available to the person.

There are nuances to all of this, but these are the basics.

Aftab: You have argued in an article in Alaska Law Review that “lawyers representing psychiatric respondents and judges hearing these cases uncritically reflect society’s beliefs and do not engage in legitimate legal processes when conducting involuntarily commitment and forced drugging proceedings. By abandoning their core principle of zealous advocacy, lawyers representing psychiatric respondents interpose little, if any, defense and are not discovering and presenting to judges the evidence of the harm to their clients.”3 Why do you think this is the case, and what do you think the lawyers representing psychiatric respondents could be doing differently?

Gottstein: Fundamentally, lawyers are appointed to represent psychiatric respondents in order to check the box that the person had a lawyer. They are not expected—and, frankly, not allowed—to present vigorous defenses. They are assigned too many cases to mount a defense, especially within the extremely compressed time frame required in these cases. The lawyers go along with it because they believe if their clients were not mentally ill, they would know what the state wants to do to them is good for them. We have what is called the “adversary system” of litigation in the US, whereby having each side’s lawyers zealously presenting evidence and arguments for their clients’ position, the neutral decision-maker—a judge or jury—is supposed to arrive at the truth and the correct result. Without that, the legal proceedings are a farce.

Lawyers assigned to represent psychiatric respondents should treat involuntary commitment and forced medication, also known as forced drugging, as the high-stakes cases they are. The state is trying to lock their clients up and subject them to mind-numbing, life-shortening chemicals they do not want, after all. One of the other things I do in The Zyprexa Papers is show how I think and go about defending these cases in the hope lawyers representing psychiatric respondents will litigate them zealously. Whether or not psychiatrists agree, they cannot accurately predict violence or self-harm—a prerequisite to commitment—and whether or not they believe the drugs are counterproductive and harmful, psychiatric respondents are entitled to have this evidence presented in court on their behalf.

The lack of effective legal representation is very harmful. People are entitled to the least restrictive alternative with respect to psychiatric confinement and the least intrusive alternative with respect to forced medication. By not challenging the proposed involuntary commitments and forced medication, people are not being allowed more humane alternatives. If people’s rights were being honored, more of these humane alternatives would have to be provided.

Aftab: The availability of psychiatric inpatient beds is quite limited in the US, at least compared to what it was like in earlier decades, and restrictions from insurance companies have drastically reduced length of stays, even for voluntary admissions. Reliance on psychiatric commitment is directly linked to the availability of viable alternatives in the community, and the failure of US psychiatry to provide such alternatives following deinstitutionalized has directly resulted in alarmingly high rates of homelessness and incarceration of individuals with mental illness. Given the current state of US politics and the pessimism surrounding the possibility of radical social reform, many in the psychiatric community are advocating for an expansion of psychiatric commitment. We can make the legal process of involuntary commitment much more arduous, as you advocate, but that only results in a good outcome if individuals with psychiatric disabilities receive meaningful accommodations and care in the community. In the absence of that, aren’t we just making the homelessness and the incarceration problem much worse?

Gottstein: That is hardly a ringing endorsement of more involuntary commitment. I think it is silly, too. Hospitalization costs what—$2000 a day? Providing housing would be far less expensive and solve a lot of the problem. Leaving the fiscal folly of the argument aside, the dysfunction, inequality, inequity, indifference, and cruelty of our society is not a legitimate excuse to lock more people up. My biggest project right now is follow-up activities to the International Peer Respite/Soteria Summit held on the 5 Sundays of last October. We are trying to use the summit as a springboard for creating and sustaining more Peer Respites and Soteria Houses around the world instead of hospitalizing people and administering medication into them against their will.

I do want to say I know I come across as being against the use of psychiatric drugs, especially the neuroleptics, and basically, I am—or at least I think we should try to minimize them—but it is the forced drugging I am against. I know people who find even the neuroleptics helpful, and if adults want to take them, they should have access to them.

Aftab: It is silly from a systemic and social perspective. Not only is it more expensive, but it is also more ethically problematic. I certainly agree that addressing social inequities, safeguarding social needs, and providing social support and programs such as Soteria Houses will prevent many, perhaps even the majority of (though not all) involuntary admissions, and I certainly think this ought to be a priority when it comes to psychiatric funding and policy. The problem, however, is not silly or illegitimate at all from the perspective of individual psychiatric clinicians who have no power over social dysfunction or social resources, but have been given the responsibility to deal with the psychiatric aftermaths of it. Decisions to hospitalize when confronted with the risk of homelessness, incarceration, serious physical neglect, or physical harm to self or others are complex, ethical questions. I am reminded of something the psychiatrist Paul Gosney, MD, said in a debate in the British Journal of Psychiatry: “Much of modern psychiatric practice feels like we are trying to rescue people from damaged lives. If one of our tools is going to be taken away, then there needs to be a corresponding commitment from society to do better by all its members.”4 Honestly, I am highly sympathetic to efforts to reduce involuntary hospitalization and for there to be robust legal safeguards, as you advocate, but I am skeptical that this on its own will result in good outcomes unless there is a corresponding commitment from society to do better by individuals with psychiatric disabilities. The need for this sort of commitment is perhaps something upon which we can both strongly agree?

Gottstein: I certainly agree on the need for that sort of commitment to noncoercive, nonharmful approaches. One of the ways to achieve that is for people to have effective legal representation because no more than 10% of people involuntarily committed actually meet commitment criteria, and nonemergency involuntary medication can never meet the legal standard of being proven by clear and convincing evidence that it is in the person’s best interest and there are no less intrusive alternatives. If the system was not allowed to psychiatrically confine the 90% of people who do not meet commitment criteria and force psychiatric drugs into people against their will, society would have to find other ways to deal with people who are disturbing and thought to be mentally ill. I think of involuntary commitment and involuntary medication as the path of least resistance for the hospital, and it should be far more difficult.

I will give you an example. After the 30-day involuntary medication order I got reversed on appeal on constitutional grounds, the Myers case was a 4-month all-out legal battle, the likes of which the hospital had never seen before—and did not like. Shortly after that, I received a call from someone who had been court ordered for a psychiatric evaluation and the hospital had to file a commitment petition against him the next morning or let him go. I contacted the CEO of the hospital and told him I did not think the person met commitment criteria and would represent him if they filed a petition to commit him. Well, they tried really hard to find something else and I never got to meet my potential client because literally as I was driving up to the hospital that evening to meet with him, he was being driven away to something less restrictive and they never filed a commitment petition.

In the Myers case, Loren Mosher, MD, the former chief of schizophrenia research at the National Institute of Mental Health and the principal investigator in the Soteria-House study, testified under oath that involuntary treatment should be “difficult to implement and used only in the direst of circumstances,” and5:

[I]n the field of psychiatry, it is the therapeutic relationship which is the single most important thing… Now, if because of some altered state of consciousness, somebody is about to do themselves grievous harm or someone else grievous harm, well then, I would stop them in whatever way I needed to… In my career, I have never committed anyone… I make it my business to form the kind of relationship [through which the mentally ill person and I] can establish an ongoing treatment plan that is acceptable to both of us.

This is the needed approach, and patients are entitled to it.

Aftab: You say that the use of “nonemergency involuntary medication can never meet the legal standard of being proven by clear and convincing evidence that it is in the person's best interest and there are no less intrusive alternatives.” Never? That is a pretty strong claim. Can you elaborate?

Gottstein: This will be a lawyer nerd answer. First, it is important distinguish the “police power” justification for forced medication versus the “parens patriae” justification. The police power justification is to stop an immediate threat of great harm. In Alaska, it is called an emergency and has very strict requirements. It is for situations like when the tiger attacking Roy Siegfried was put down with a shot of Haldol. In contrast, the parens patriae justification is based on a judicial determination the person is incompetent to make a decision about the medication, and therefore, the government must step in in the nature of a parent and make the decision for the person in their best interest.

The legal standard for that is to prove by clear and convincing evidence it is in the person’s best interest and there are no less intrusive alternatives. I do not believe either can be proven by the clear and convincing standard which has various definitions depending on the state, but basically means “highly probable.” As an aside, in the United States Supreme Court case of Addington v. Texas, the psychiatric patient argued since the state was seeking to lock him up like a criminal, they should have to prove the right to do so beyond a reasonable doubt. The Supreme Court held psychiatrists could never prove their case beyond a reasonable doubt and since the confinement was not for a punitive purpose, they had to prove it by clear and convincing evidence instead, which is a higher bar than the more likely than not standard in other types of civil cases. This was for involuntary commitment, but it has been held the same standard applies to involuntary medication. This does vary by state, but I think it is the correct constitutional standard.

In my view, based on the evidence, the state can never prove it is highly probable that forcing psychiatric drugs into an unwilling patient is in their best interest in light of the abysmal outcomes and physical harm they cause, including early death. I also do not think it can legitimately be proven by clear and convincing evidence there is no less intrusive alternative that could be provided. I know people may disagree with me and, in fact, I tended to lose at the trial court level. I think that was because of the practical problem there was no actual less intrusive alternative to which my client could be sent. I write in The Zyprexa Papers about my last case representing Bill Bigley, where I had presented the evidence and the judge ordered Bill be drugged against his will anyway, ruling, “Even if the medication shortens Bigley’s lifespan, the court would authorize the administration of the medication because Bigley is not well now and he is getting worse.” So, I know many people disagree with me, including probably most of the people who will read this, but it is my view no legitimate determination can be made that it is highly probable forcing psychotropic medication into someone is in their best interest and there is no less intrusive alternative. It is hard for me to accept that shortening Bill Bigley’s life was in his best interest.

Aftab: I want to say for the record that, as a clinician, I am not persuaded by your stance on the involuntary use of medications, and based on my experience of working with the courts, neither are they, but I appreciate your engagement, and I am sure your arguments will give many readers much to think about. Thank you!

Dr Aftab is a psychiatrist in Cleveland, Ohio, and clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University. He leads the interview series “Conversations in Critical Psychiatry” for Psychiatric Times™. He has been actively involved in initiatives to educate psychiatrists and trainees on the intersection of philosophy and psychiatry. He is also a member of the Psychiatric TimesTM Editorial Board. He can be reached at awaisaftab@gmail.com or on Twitter (@awaisaftab).

Dr Aftab and Mr Gottstein has no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References

1. Berenson A. Eli Lilly said to play down risk of top pill. The New York Times. December 17, 2006. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/17/business/17drug.html

2. Healy D. The Zyprexa Papers: this book had to be written. Samizdat Health. March 21, 2020. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://samizdathealth.org/zyprexa-papers/

3. Gottstein JB. Involuntary commitment and forced psychiatric drugging in the trial courts: rights violations as a matter of course. Alaska Law Review. 2008;25:51.

4. Gosney P, Bartlett P. The UK Government should withdraw from the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;216(6):296-300.

5. Faith Myers v. Alaska Psychiatric Hospital. http://psychrights.org/states/alaska/caseone/30-day/3-5and10-03transcript.htm

Medical students are just now starting their yellow brick road journey…

Merggy/AdobeStock

PSYCHIATRIC VIEWS ON THE DAILY NEWS

In yesterday’s column, I called for more psychiatric stories. On the day before, I had watched one of the greatest (psychiatric) stories of all time. For my wife’s birthday on July 28th, we went to see a musical version of the “Wizard of Oz.” Not only was the one we saw an inventive and inspiring performance, but I finally got a sense of the deep psychological meanings of what is often viewed as a children’s story.

In the beginning of Oz, Dorothy walks off from her home after repeatedly getting into trouble and having her dog Toto taken by a mean neighbor and citizen of power. Somewhere there is a rainbow, she sings, but first she has to encounter a climate changing tornado, and after many Jungian archetypal obstacles and challenges, ends up meeting the so-called Wizard of Oz. She then gets home, as if waking from a dream.

Around the same time, I was grappling with the videos of the white coat ceremony on July 24th of a large number of new medical students at our alma mater, the University of Michigan. They left in protest of the keynote speaker, Kristin Collier, MD, apparently because of her “pro-life” stance regarding abortion and their defense of social medical justice. Although they asked for a replacement, the leadership confirmed her participation. Ironically, Dr Collier was picked by the honors society, which had included medical students, because she was a beloved teacher and head of the spirituality, religion, and health programs, but that choice was made before the formal end of Roe v Wade.

In Dorothy’s Campbellian heroic journey over the yellow brick road, she is accompanied by a scarecrow, tin man, and lion, who are in search of their brain, heart, and courage, respectively. By the end, in a cognitive behavioral therapeutic reframing, they come to realize they always had those powers, but had not realized or used them.

Reading up more about Dr Collier, she described going on her own heroic journey. Coming to the medical school 17 years ago as a liberal “pro-choice” atheist, over time she converted to Christianity, and in 2018 became “pro-life.” For her keynote, she said in advance that she was not going to comment on her private religious beliefs, nor on this controversial subject, and she did not. Instead, she focused on the general issue of how medicine is becoming more technological and under the assumed control of business, whereby physicians and patients distressingly have less therapeutic choices. After the keynote, when the walk-off students were being harassed, she asked for that to stop.

The medical students, both those who walked off and who did not, are just beginning their yellow brick road ethical journey in a time of a physician burnout epidemic. I hope there is follow-up discussion and processing for all concerned, perhaps to include a screening of “The Wizard of Oz.”

Dr Moffic is an award-winning psychiatrist who has specialized in the cultural and ethical aspects of psychiatry. A prolific writer and speaker, he received the one-time designation of Hero of Public Psychiatry from the Assembly of the American Psychiatric Association in 2002. He is an advocate for mental health issues related to climate instability, burnout, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism for a better world. He serves on the Editorial Board of Psychiatric Times™.

Does being a good storyteller make you a better clinician?

Chinnapong/AdobeStock

PSYCHIATRIC VIEWS ON THE DAILY NEWS

A colleague recently wondered why we in psychiatry do not tell enough stories about ourselves and our work. He had just read—and forwarded to me—the book review by Jerome Groopman, MD, in the July 25, 2022 New Yorker, titled “Why Storytelling Is Part of Being a Good Doctor.”1 The review began with Dr Groopman discussing how he came to be a popular writer of moving medical stories about life, death, and uncertainty after being a writer of the usually drier academic articles. The review then focused on the Chief of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Jay Wellons, MD, MSPH, and his mid-career memoir of All That Moves Us. Such emotionally laden stories are what we all tend to remember over facts and figures, as important as those facts and figures may be in their own right.

Dr Groopman, in passing, touched upon many other physician writers. As usual, I noted that none of them were psychiatrists. Isn’t that strange at first glance? Here we can be in our close interpersonal relationships with patients who often share the gory and glory of their lives. Certainly, this was not the case in the time of Freud and his colleagues. Irving Yalom, MD, in our time has been one of the notable rare exceptions. With a similar academic background as Dr Groopman, I eventually tried to use the story conceit of a mock company when I was asked to write a book about the emotionally laden challenge of ethics in managed care.2

Is our current reluctance to tell our stories the result of ethical confidentiality concerns? That should not be the case since we can disguise identity. Is it in part the spin-off influence of our Goldwater Rule against commenting on public figures and their public stories? We do not even seem to appear on the major media medical discussions of psychiatric topics. Is it because we have become more of a 15-minute med check provider devoid of interesting stories?

Last year, I wrote the Forward to the beautiful book, STORY story, with text by William Cleveland and artwork by Barry Marcus. It conveys a primal story with primal images. I now wonder: What is the primal story of psychiatry? Maybe you would like to share what you think that is.

To paraphrase Dr Seuss: Oh, the mental places we’ve gone! I am sure many of you have all kinds of psychiatric stories, short or long, to tell, too.

Dr Moffic is an award-winning psychiatrist who has specialized in the cultural and ethical aspects of psychiatry. A prolific writer and speaker, he received the one-time designation of Hero of Public Psychiatry from the Assembly of the American Psychiatric Association in 2002. He is an advocate for mental health issues related to climate instability, burnout, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism for a better world. He serves on the Editorial Board of Psychiatric Times™.

References

1. Groopman J. Why storytelling is part of being a good doctor. The New Yorker. July 18, 2022. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/07/25/why-storytelling-is-part-of-being-a-good-doctor-all-that-moves-us-jay-wellons

2. Moffic HS. The Ethical Way: Challenges & Solutions for Managed Behavioral Healthcare. Jossey-Bass; 1997.

With so much media surrounding mass violence in the US, we need to sort out fact from fiction.

Антон Фрунзе/AdobeStock

It would be nearly impossible to peruse any media, engage in any conversation, or interact in any workplace without coming across the topic of the increased number of mass violence episodes (usually mass shootings) in the United States. With this in mind, I wanted to share evidence and thoughts surrounding myths about these episodes… as well as their corresponding truths. Although this is important in terms of accuracy, it is even more germane as it pertains to appropriate messaging by psychiatric professionals to our patients and our communities.

Myth #1: “We live in a more violent world than ever.”

Although the number of firearm deaths is increasing (please see Myth #7), we have seen decreases over time of other violent events. This is important to many of our patients suffering from anxiety or trauma-based illnesses. This myth and its messaging can lead to worries regarding lack of control, fatalistic projections, and learned helplessness. Additionally, it is important to note that most of the violence in the United States is not categorized as mass shootings. For instance, approximately 70 women are killed with firearms every month in situations of domestic violence.1

Myth #2: “All of these perpetrators are mentally ill.”

The truth is that the majority of the individuals acting as mass shooters do not possess diagnosable or treatable mental illnesses. In other words, mass shootings are not predominantly attributed to those with mental illness. In fact, it is much more common for those living with mental illness to be a victim of a crime, not the perpetrator.2 If you examine all violent events, only a very small percentage (3% to 4%) are committed by individuals with mental illness. Although that number rises a bit when looking solely at incidents of mass violence, it is still quite small when looking at the overall data set (15% to 20%).3,4

Myth #3: “Patients with severe and persistent mental illness are routinely dangerous.”

Debunking this myth is massively important; we need to properly message this to decrease stigma, increase access, and provide a safe community for those with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI). Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that the majority of those with mental illness are not violent,5 and even more so, there is little to no evidence that there are high rates of firearm violence directed to others. On the rare instances in which violence is seen in the SPMI population, it is not usually perpetrated with guns, and it is not directed toward strangers and the general public.6 The 3 main items that tend to correlate as predictive factors for homicidal violence (whether one has a mental illness or not) is anger, intoxication, and access to firearms.7

Myth #4: “Mass shootings are the most prevalent violent issue facing society now.”

Although episodes of mass violence are low incidence events (compared to all violent events), they are very powerful in terms of emotion, victims, and media coverage. In fact, other violent acts occur much more frequently. For instance, there were approximately 500 deaths from mass shootings between 2000 and 2016. During that same time period, there were almost 320,000 suicide firearm deaths.8 Moreover, recent data has shown the suicide numbers to be at least twice that of all homicides.8 Thus, from a public health standpoint, the rise in suicides dwarf that of homicides and other violent deaths (not just mass shootings).

Myth #5: “Enacting legislation focused on the mentally ill will decrease mass shootings.”

Part and parcel to Myth #2, this makes mathematical sense as there would not be significant change by focusing on 15% of the cases. By falsely looking at mental health, we are missing characteristics that have been found to be markedly more common in assailants, including domestic violence, misogyny, and feelings of isolation and alienation (with rumination on perceived slights, particularly in the workplace). Additionally, most individuals who commit these shootings exhibit planning/practicing and cognitive appraisal. These actions are not consistent with psychosis, which is associated with the inability for self-care, nor would these traits be detected by present civil commitment statutes.9

Myth #6: “Mental health screening and risk factors are the best way to predict mass shooting events.”

Very similar in tone to Myth #5, Federal Bureau of Investigations data has shown perceived victimization, rumination, and premeditation amongst perpetrators is more indicative of intent than mental health status. Similarly, Secret Service data has noted personal grievances, past violence, and a history of felonious events as predictive.10 As such, the most common predictors are not symptom domains normally seen in psychiatric illness. That being said, we have a lot to offer the field given our skills in risk assessment, interviewing, and inter-agency collaboration.

Myth #7: “Access to firearms is not a risk factor for episodes of mass violence.”

Although this topic comes with a great deal of emotion and history, it is noted to be an important part of messaging any conversation around mass violence. The US firearm homicide rate (from all causes) is 25 times higher than our peer high-income countries.11 Not surprisingly, the US gun death rate per 100,000 citizens is 3.24 compared with an average of 0.19 from our peer countries. Combine this with the fact that the United States has 44% of the world’s firearms (while only having 4.4% of the world’s population).12 Thus, it can be noted that American crime, in general, is more lethal than peer countries.

Myth #8: “Laws and policies addressing firearm access will not mitigate the risk of mass violence.”

Extreme risk protection orders in several states have been noted to reduce population level firearm suicide rates.13 Another intervention strategy is banning large capacity magazines. Interestingly, states without such bans have seen increased incidence of mass shootings and higher fatality rates when shootings occurred.14 Lastly, state legislation focusing on firearm restraining orders resulted in a 10% decreased intimate partner violence.15

From a suicide risk mitigation perspective, this degree of effect is consistent with the Lethal Means Safety literature,16 which notes that individuals do not displace aggression (ie, they do not just find another way). Consequently, legislation pertaining to firearm access has the ability to reduce several categories of gun violence (eg, suicide, mass homicide, and intimate partner violence).

Myth #9: “Schools are markedly more violent/dangerous than ever before.”

This is another dangerous misconception that can lead to more harm than good. Although the media focuses on this extensively, the actual numbers of school shootings pale in comparison to other violent acts, like suicide or intimate partner violence. In fact, you are 10 times more likely to encounter violence at a restaurant compared to school, and 100 times more likely to encounter violence in your own home.17

Myth #10: “Focusing solely (or primarily) on mental illness issues with regard to mass shootings does no harm, right?”

Wrong. Using mental illness as the primary focus in these scenarios is not only inaccurate (as described previously) but it is also quite stigmatizing. In addition, when media coverage focuses on mental health as the driver in these tragedies, there is also a delayed wait time to enter outpatient psychiatric services (the irony). For example, a data set from 1997 to 2012 revealed that news sources focused on “dangerous people with illness” more so than “dangerous weapons.”18

Practical Implications

Now that we better understand these myths as well as the proper messaging to combat them, what do we do next as a profession? In other words, just because the majority of these cases are not perpetrated by individuals with primary mental illness, it does not mean that the field of psychiatry does not have a part to play—or that we should not be active in the conversation.We need to be involved in assistance, assessment, and we need to be present on the rare cases in which these events do involve someone with mental illness.

The field of threat assessment is an excellent example of a collaboration involving law enforcement, mental health, and several other federal agencies. They have many excellent suggestions regarding notification (ie, “if you see something, say something”) as well as reminding anyone involved to “never worry alone.”19 Many of the individuals who commit these crimes do not snap, but instead plan and prepare for months preceding the incident. Hence, there are instances of direct sharing of plans, and other times, more indirect “leaking” of intent.20 Threat assessment teams allow for longitudinal analysis and observation of individuals with these risk factors. Our field has an excellent opportunity to work with such stakeholders to improve identification and follow-up in such cases.

Concluding Thoughts

We have an important role in educating others about these 10 common misconceptions pertaining to mass violence. We must leverage solid research and data to help paint a more accurate picture. The reason we need to discuss the truth behind these issues is not only for the purpose of clarity but also to make sure that we are messaging appropriately in our advocacy and support of our mission. In doing so, we are advocating for not only our profession, but also for our communities at large.

Dr Thrasher is the president of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry (AAEP), the medical director of crisis services in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, and president elect of the Wisconsin Psychiatric Association.

References

1. Everytown analysis of CDC, National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), 2019. https://everytownresearch.org/maps/mass-shootings-in-america/#domestic-violence-was-a-part-of-most-mass-shootings

2. Brekke JS, Prindle C, Bae SW, Long JD. Risks for individuals with schizophrenia who are living in the community. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(10):1358-1366.

3. CDC Leading Cause of death reports. National and regional 1999-2010; February 2013.

4. Metzl JM, MacLeish KT. Mental illness, mass shootings, and the politics of American firearms. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):240-249.

5. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

6. Gun violence and victimization of strangers by persons with a mental illness: data from Macarthur Studies. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(11):1238-1241.

7. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Silver E, et al. Rethinking Risk Assessment: The MacArthur Study of Mental Disorders and Violence. Oxford Press; 2001.

8. Injury Prevention and Control: Data and Statistics (WISQARS); CDC, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

9. Swanson JW. Explaining rare acts of violence: the limits of evidence from population research. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;62(11):1369-1371.

10. “Mass Violence in America: Causes, Impacts and Solutions.”National Council for Behavioral Health, Medical Director Institute, August 2019.

11. Fox K. How US gun culture compares with the world in 5 charts. October 3, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.wral.com/how-us-gun-culture-compares-with-the-world-in-5-charts/16993476/

12. Fisher M, Keller J. Why does the U.S. have so many mass shootings? The New York Times. November 7, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/07/world/americas/mass-shootings-us-international.html

13. Kivisto AJ, Phalen PL. Effects of risk-based firearm seizure laws in Connecticut and Indiana on suicide rates, 1981–2015. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(8):855-862.

14. Klarevas L, Conner A, Hemenway D. The effect of large-capacity magazine bans on high-fatality mass shootings, 1990–2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(12):1754-1761.

15. Zeoli AM, Webster DW. Firearm policies that work. JAMA. 2019;321(10):937-938.

16. Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:193-199.

17. Nekvasil EK, Cornell DG, Huang FL. Prevalence and offense characteristics of multiple casualty homicides: are schools at higher risk than other locations? Psychology of Violence. 2015;5(3):236-245.

18. McGinty EE, Webster DW, Jarlenski M, Barry CL. News media framing of serious mental illness and gun violence in the United States, 1997-2012. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):406-413.

19. Thrasher T. Debunking 4 myths around mass shootings. Psychiatric Times. April 12, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/debunking-4-myths-around-mass-shootings

20. Averting Targeted School Violence: A U.S. Secret Service Analysis of Plots Against Schools. US Department of Homeland Security, United States Secret Service, National Threat Assessment Center. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.secretservice.gov/sites/default/files/reports/2021-03/USSS%20Averting%20Targeted%20School%20Violence.2021.03.pdf

The loss of these 2 psychiatrists resonates.

muh23/AdobeStock

IN MEMORIAM

Though difficult to define, synchronicity often refers to the simultaneous occurrence of events which seem significantly related but have no obvious casual connection. It can seem like the symbolic trail that leads to a new destination. Spiritually speaking, it can refer to being guided toward something beyond yourself. Carl Jung took synchronicity into the psychological realm of meaningful coincidences, though sometimes the meaning can seem elusive. Sometimes, it seems, you just know it when you experience it.

Personally, synchronicity has been of increasing fascination and importance to me in recent years. Ever since the Jewish High Holy Days during October 2019, it seems that synchronicity has happened to me more or less daily, even guiding what I write about.

Now synchronicity has come to the intermittent eulogies I write. Whether sacred or secular, it seems to me that these 2 eulogies are of divine psychiatric careers.

Jan Fawcett, MD

Jan Fawcett, MD: Creative Synchronicity

Dr Fawcett died on May 9, 2022, the day after Mother’s Day, at the age of 88.

He received his MD at Yale Medical School in 1960, as I did in 1971, both of us still during the period when there were no tests during medical school there. Besides that connection in our informal relationship, we ended up with some overlapping research interests. During medical school, my required research project was about depression in medical inpatients and later published; later, Dr Fawcett found that severe combined depression and anxiety was a significant risk factor for suicide in psychiatric inpatients.

Dr Fawcett became well-known as a leader and innovator in the area of mood disorders. That expanded into the realm of expert court testimony about depression and suicide. One notable example was testifying against Jack Kevorkian, MD, and his medical assistance in dying, concluding that many of those patients had untreated, but treatable depression.

Dr Fawcett received many awards for his work on mood disorders, but also established an award for residents when he was Chair of Psychiatry at Rush Medical School in Chicago. The “Dr Fawcett Was Wrong Award” was given to those who found research contradicting something he had taught them.

What I liked best in his career was his position as the editor of Psychiatric Annals. I sometimes read the articles in a given issue, but always read his 1-page editorials. And this is where scholarly synchronicity comes in. Searching for an example to share in this eulogy, I quickly ran across the May 2009 special issue on, yes, synchronicity—a rarely covered topic in psychiatry, then and now. It was guest edited by Bernard Beitman. Articles included “Synchronicity, Weird Coincidences, and Psychotherapy,” “Synchronicity and Psychotherapy: Jung’s Concept and Its Use in Clinical Work,” and “Clinical Implications of Synchronicity and Related Phenomena.”1-3

Dr Fawcett’s Editorial was, as usual, innovative and titled “Creative Synchronicity in Treatment and in Other Human Relationships.”4 He extended the usual definition to include a creative intent to consciously act to reinforce a positive state in another individual, especially as a psychotherapeutic addition to the prescribing of medication.

When he was told one day that his malignant melanoma was free of metastases, he had an epiphany, left Rush and moved to Santa Fe “to watch sunsets” and write a science fiction novel titled Living Forever, based on his own illness and life changes. For sure, he at least lives on in the expert knowledge he conveyed, the charismatic inspiration he gave, and the grateful people he helped.

Robert Daly, MD

Robert Daly, MD: Synchronicity in a Mentor and Mentee

July 4th, our country’s Independence Day, always has special meaning, but seemingly more so this year in regard to psychiatrists. On that day, the mass shooting during a parade in Highland Park received national attention. I added a few reflective daily columns on it for Psychiatric Times™.

A few days later, I found out from our Editor-in-Chief Emeritus, Ronald Pies, MD, that the psychiatrist Robert Daly, MD, also died on that day at the age of 89. As I reviewed his career in his obituary, it seemed full of humanism as well as a broad range of psychiatry. He became a Professor of Psychiatry and Bioethics and Humanities at SUNY Upstate Department of Psychiatry in Syracuse, where he worked for 40 years. While there, he helped establish the Consortium for the Cultural Foundation of Medicine and the Institute for Ethics in Health Care, speaking on these subjects around the world. In his work-life balance, he spent time with his family, friends, sports, and Holy Cross Church.

Dr Pies communicated this to me about him:

“Bob Daly was one of my mentors during residency, and—along with Gene Kaplan—one of the foremost influences on my career. One comment from Bob that deeply affected me and confirmed my choice of psychiatry as a specialty: ‘With psychiatry, you can do biology in the morning and theology in the afternoon!’ I will sorely miss him.”

He felt a bit like Socrates to Dr Pies in his wisdom, principles, and brilliance, but likely friendlier. I can see why. I would just add to the quote that at dinner you can then discuss the spirituality in psychiatry and the psychiatry in spirituality.

The important relationship of Drs Daly and Pies continued over the years. Perhaps it reached it reached one of its zeniths in a joint article for Psychiatric Times™ on March 4, 2010, titled “Should Psychiatry and Neurology Merge as a Single Disciplines?”5 It was based on a Grand Rounds at Syracuse from August 27, 2009. In support of the resolution was Dr Pies; in opposition was Dr Daly. I would conclude that the real winner of this debate was their relationship and us readers. Certainly, Dr Daly’s legacy lives on in Dr Pies and so many others that he influenced and helped.

Epilogue

Whether you believe in the importance of synchronicity or not, the lives of both Drs Fawcett and Daly had significant meaning professionally and personally. And whether there was any divine intervention in their passing away at similar ages and similar times, they both remind us of the humanity and ethics necessary to supplement the benefits of hard science and to counter the inhumanity of mass shootings. For me, they exemplify the range of what psychiatry can—and should—cover, from neurology to cultures, and from the needs of the individual patient to the needs of society.

Their lives were a psychiatric blessing.

Dr Moffic is an award-winning psychiatrist who has specialized in the cultural and ethical aspects of psychiatry. A prolific writer and speaker, he received the one-time designation of Hero of Public Psychiatry from the Assembly of the American Psychiatric Association in 2002. He is an advocate for mental health issues related to climate instability, burnout, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism for a better world. He serves on the Editorial Board of Psychiatric Times™.

References

1. Beitman BD. Synchronicity, weird coincidences, and psychotherapy. Psychiatr Ann. 2009;39(5):245-246.

2. Hopcke RH. Synchronicity and psychotherapy: Jung’s concept and its use in clinical work. Psychiatr Ann. 2009;39(5):287-293.

3. Nachman G. Clinical implications of synchronicity and related phenomena. Psychiatr Ann. 2009;39(5):297-308.

4. Fawcett J. Creating synchronicity in treatment and in other human relationships. 2009;39(5).

5. Pies RW, Daly R. Should psychiatry and neurology merge as a single disciplines? Psychiatric Times. 2010;27(3).

Habits or addictions? COVID-19 changed the game.

Maridav/AdobeStock

If the reasonable person on the street was asked to define “a habit,” they might shrug their shoulders and be at a loss for words. According to Laura Araujo, cofounder of the Mindfulness, Activation, Purpose, and Surrender (MAPS) Institute, habits are nonverbal, automatic behaviors associated with the prefrontal cortex that take on average 66 days to become ingrained. Habits are not necessarily associated with higher cognition, in contrast to routines, which are planned sequences of behavior.1

Contemplating how our daily habits and routines have been impacted by COVID-19 has become national pastime, if not consciously then at least subconsciously. Especially now that we are undecided about whether the pandemic is over, many of us are left wondering what exactly our new behavioral patterns should be.

It can become quite overwhelming to think about this. A 2020 survey of 8000 adults conducted in the greater Tokyo area showed that 33 % of male respondents and 34% of female respondents experienced an increase in sedentary activities since the onset of the pandemic, while, conversely, 17% and 18% of men and women respectively reported a decline in daily physical exertion along with self-reported changes in health status.2

Cognitive therapists have spent considerable effort constructing models for habits and routines. Habits are triggered by various types of cues and are known to become automatic over time. While routines are volitionally created, they too can become automatic given sufficient impetus. And habits, as well as routines, can swing the pendulum from adaptive to off-putting, thoughtful to reckless.3 Henceforth, the focus will be on adaptive habits and routines.

Several of my associates have remarked on the need to rebuild socialization stamina, rusty from months of lockdown and somewhat analogous to the professional athlete in re-training. For Miriam Lavine, LCSW, director of a community mental health program, the opposite has actually been true. “Before the pandemic,” reflects Ms Lavine, “I may have taken collegial gatherings for granted. But now, where there is an event, I find that socializing and reestablishing with others is anything but tiring, and I am aware of how normal and pleasant it all seems.”

Case Vignette

Some routines have been unaffected by COVID-19, as illustrated by this story.

At the close of a prepandemic session, “Ms Young,” lamented on her boyfriend’s habit of watching sports over the weekend. She reported an impending feeling of exclusion on Friday evenings as she anticipated competition with the ESPN channel, and yet was afraid to speak up as the relationship was still brand new. When asked whether she believed a compromise was possible, given hers and her boyfriend’s mutually hectic weekday schedules, Ms Young responded, “Honestly, I doubt it, doctor. We are dealing with something powerful here. Let’s discuss this again. Thanks so much.”

Ms Young described her partner’s intense devotion to TV sports—the major leagues, professional golf, and the Stanley cup playoffs—in a good-natured manner. While “sports addiction,” never entered the dialogue, I could not help but reflect on the term based on some of my own experience.

According to Nora D. Volkow, MD, Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and renowned researcher on the neural mechanisms of substance abuse, while terms like “addicted” and “obsessed” permeate our everyday conversation as part of a compelling narrative, the risk for the public is a misperception of just how serious clinical addiction can be.

Dr Volkow further explains that, “The challenge in sorting out routines from true compulsions is that in both cases we are dealing with normal and pleasurable aspects of life, such as eating or making a purchase.”

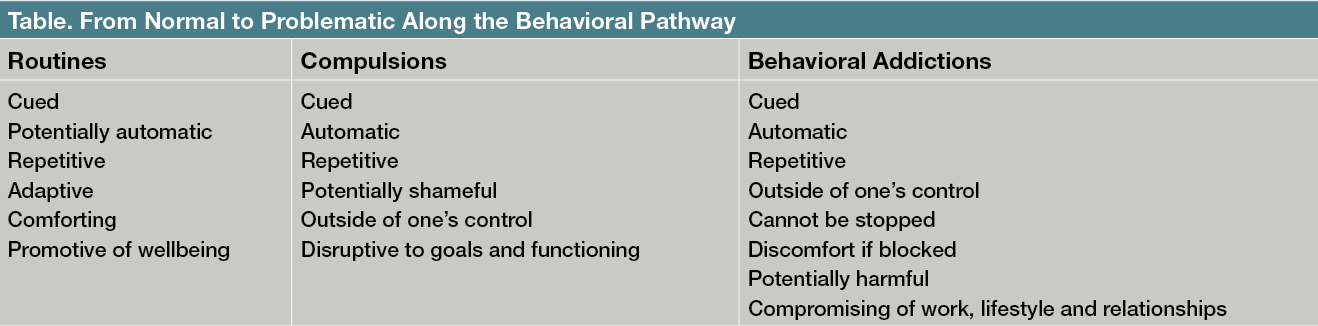

“Plus,” adds Dr Volkow, “behaviors do not necessarily set up as powerful brain circuits as do drugs which hijack the reward pathways in the ventral area of the brain’s prefrontal cortex. The key distinction is whether the person can no longer control that particular behavior such that it becomes deleterious.” (Table)

Table. From Normal to Problematic Along the Behavioral Pathway

To a certain extent, the concept of a behavior veering into “addictive” carries some degree of elusiveness. How do everyday routines blithely transform into compulsions and what are the risk factors? How does the wellness routine of yoga practice, for instance, turn into something nightmarish, a question I once posed to a certified yoga instructor? Her response was incredibly straightforward. “I do not think yoga is addictive if you do not have an addictive personality.”

In the DSM-5, the only recognized behavioral addiction under nonsubstance-related disorders is gambling.4 Yet, we find that shopping, eating, intimacy, video gaming, and posting on social media can all be grouped under the umbrella of behavioral addictions when taken to the extreme.5,6 There is also excessive body building, sometimes accompanied by the use of anabolic steroids and disordered eating, due to the condition of bigorexia, a belief that one’s muscle mass is inadequate.7

Since the start of the pandemic, the newspaper for me has become central towhat I view as an adaptive routine. Some might argue that reading the newspaper is obsolete, given all the available news feeds on smart phones. However, I duly admit that holding a daily paper with coffee in hand, is a comforting ritual. Scanning the front section for international news, then the second section for pandemic metrics, followed by all the cultural happenings allows a connection to the greater world despite its problems and upheavals.

You may ask yourselfwhat has changed in your own lifestyle during the pandemic? Take a glance within. I would invite you to honor all of those daily routines that promote strength and purpose, that maintain an internal sense of structure. This process can also be applied when treating patients experiencing any degree of stress. The key is to avoid harsh self-appraisals and over-analysis, particularly during this continued time of uncertainty. In closing, I would remind the reader that adaptive routines are necessary and never compulsive if conducted with intention and balance.

Acknowledgements: The author would like the thank the following individuals: Yi Zhou, MLIS, and the library staff of Morristown Medical Center; Nora D. Volkow, MD; Miriam Lavine, LCSW; and Mr Jon W Green, esq.

Dr Sofairis a board-certified psychiatrist affiliated with CarePoint Health and Atlantic Health System in New Jersey.

References

1. Araujo L. Understanding the difference between routine and habit and why it’s critical to our functionality. May 7, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://themapsinstitute.com/understanding-the-difference-between-routine-and-habit-and-why-its-critical-to-our-functionality/

2. Suka M, Yamauchi T, Yanagisawa H. Changes in health status, workload, and lifestyle after starting the Covid-19 pandemic: a web-based survey of Japanese men and women. Environ Health Prev Med. 2021;26(1):37.

3. Le Cunff A-L. Habits, routines, rituals. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://nesslabs.com/habits-routines-rituals

4. Gambling disorder under non-substance-related disorders. Desk Reference to yhe Diagnostic Criteria From DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013:282-283.

5. Kar A, Adikey A, Wells J, Kablinger A. Obsessive-compulsive disorder driven by aspects of ritual addiction: a case report and review of the literature. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2021;51(2):65-68.

6. Luigjes J, Lorenzetti V, de Haan S, et al. Defining compulsive behavior. Neuropsychol Rev. 2019;29(1):4-13.

7. Martyniak E, Wyszomirska J, Krzystanek M, et al. Can’t get enough. Addiction to physical exercises: phenomenon, diagnostic criteria, etiology, therapy and research challenges. Psychiatr Pol. 2021;55(6):1357-1372.